|

During the WWII, in the name of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan gradually encroached upon French Indochina, British North Borneo, Dutch Indonesia, the Philippines and others. With the expansion of the empire, many traveled to Nanyang to explore the local conditions and report the war. “Nanyang” indicates a geographical region that corresponds to today’s Southeast Asia. From the period of Ming and Qing Dynasties onwards, Nanyang had been a destination of Han Chinese immigrants, forming a highly interconnected trade network and an economic community to be reckoned with. In the 19th century, Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States incorporated Nanyang into their colonial empire and Burma, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines all fell under colonial control. The Sino-Japanese War from 1937 ushered in a period of the vigorous execution of the Southward Expansion Doctrine by Japan, with the invasion of southern China and Nanyang beginning to take place. Unfurling the banner of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan sought to “liberate Asia from the yoke of Western Powers” under Japanese leadership and build a united political entity for a “new order of co-prosperity”, becoming in reality the pretext for Japanese imperial expansionism. In September 1940, to prevent the possibility of assistance to Kai-Shek Chiang by way of French Indochina, the Japanese invaded Vietnam. In the wake of the Pacific Theater of the WWII in 1941, the Japanese forces also occupied British North Borneo, Dutch Indonesia and the Philippines, starting an investigative project for various regions of Nanyang. Against this backdrop, the serialized accounts of travel published by “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” came to include those about Nanyang, which amounted to 11 accounts and about 40 articles. They encompassed the activities of Tung-Lan Chang as an interpreter in Burma, Yuzo Maeda and Kiyoto Takeuchi as correspondents for French Indochina and several war correspondents and economically oriented investigative groups who trailed the shifting frontiers of the empire deep into Java, Borneo, Sulawesi and others, observing the implementation of military and political schemes and constructions in various regions. This piece focuses on the activities concerning Burma and Vietnam.

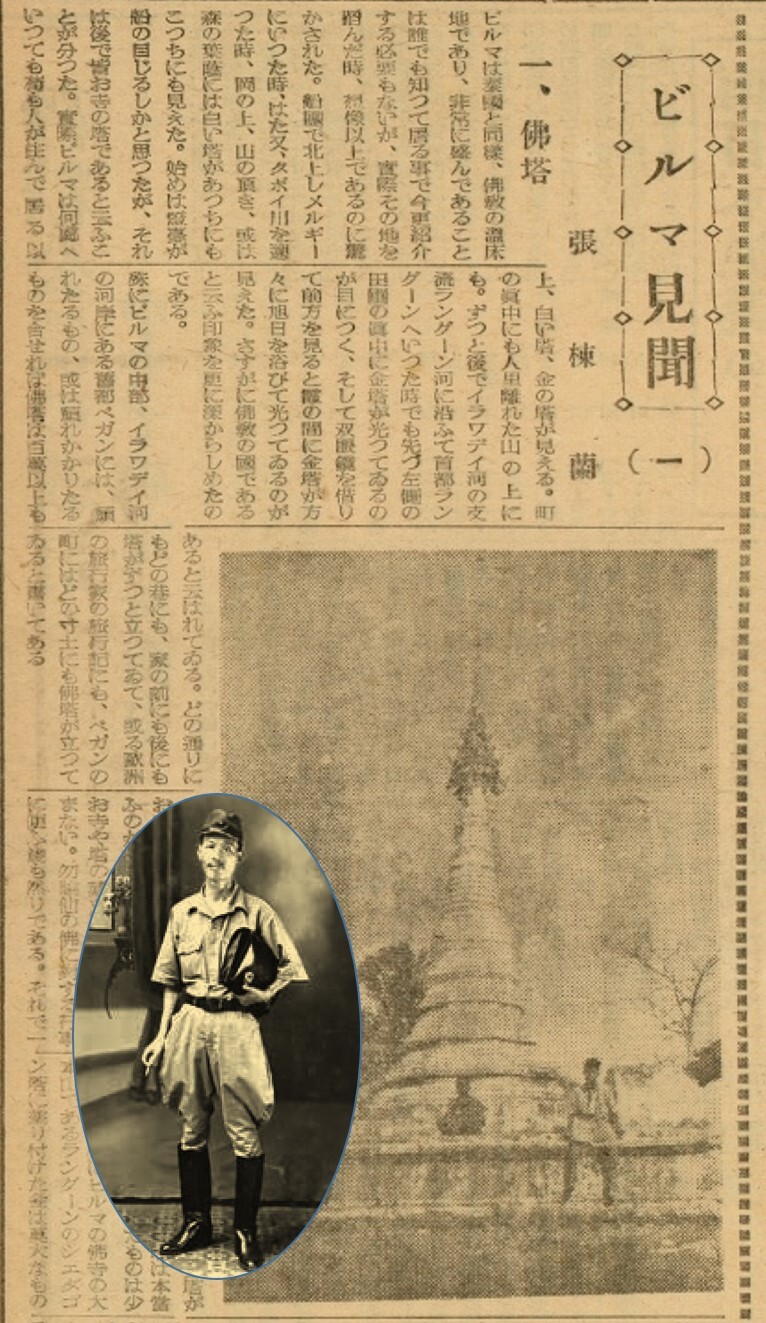

In November 1940, Tung-Lan Chang, an English teacher from the National Hsinchu Senior High School, traveled to Nanyang to serve as an interpreter as a matter of imperial policy. Of the same group of people journeying as far as Nanyang for the same purpose, he was the only Taiwanese. Tung-Lan Chang first went to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and did not move to Burma until May 1942. On the same ship to Burma were Australian prisoners of war and a battalion of Japanese soldiers tasked with the construction of the railways. Tung-Lan Chang was himself charged with English interpretation, learning the Burmese language to help Japanese soldiers to acquire the language and setting up a Japanese school for the Burmese people. After one year and half of such interpretation works, he was finally sent back to Taiwan in 1943. His account of travel was serialized by “Shing Nan News” in three articles starting on 6 May 1943. Tung-Lan Zhang, from Hukou, Hsinchu, graduated from the Dahukou Public School and the Taichung Middle School before moving to Japan to study English with the Faculty of Letters in the Waseda University. He began teaching English in the National Hsinchu Senior High School, becoming the first Taiwanese teacher serving with the school since its founding. He was dispatched to Nanyang during the WWII to serve as an English interpreter and returned to Taiwan towards the end of the war to continue his teaching career in the National Hsinchu Senior High School. In the post-war period, he served as an adjunct professor at the National Taiwan University and the principal of the Hsinchu Junior High School. He also worked with the Archives of the Hsinchu County.

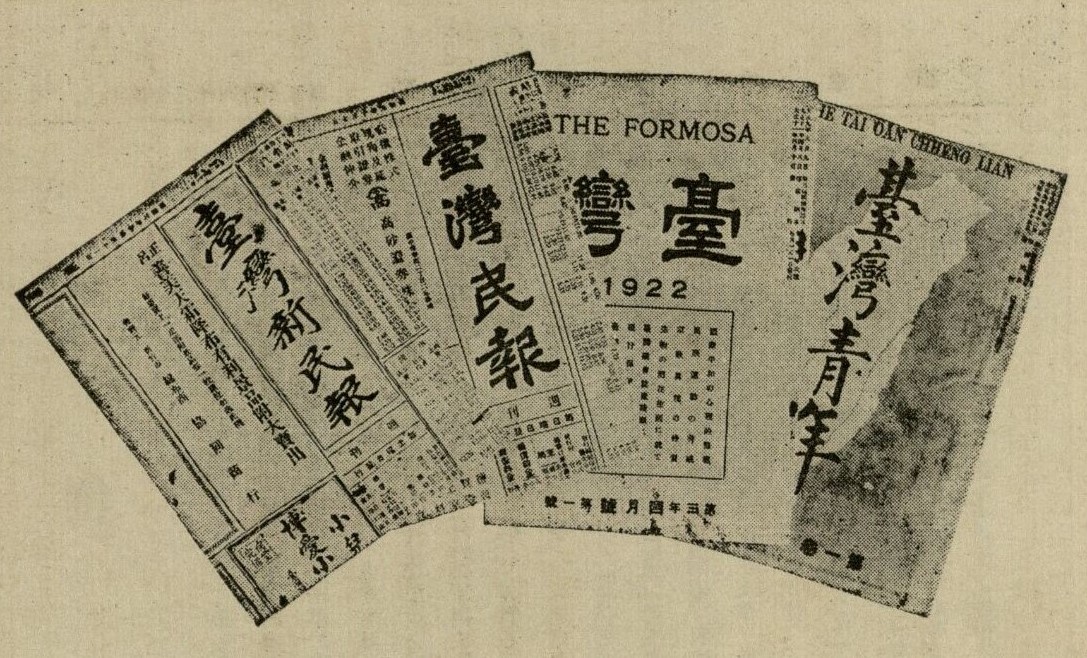

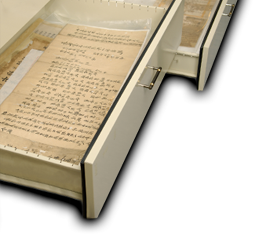

Figure 48: Tung-Lan Chang’s Account of Travel Published in “Shing Nan News”

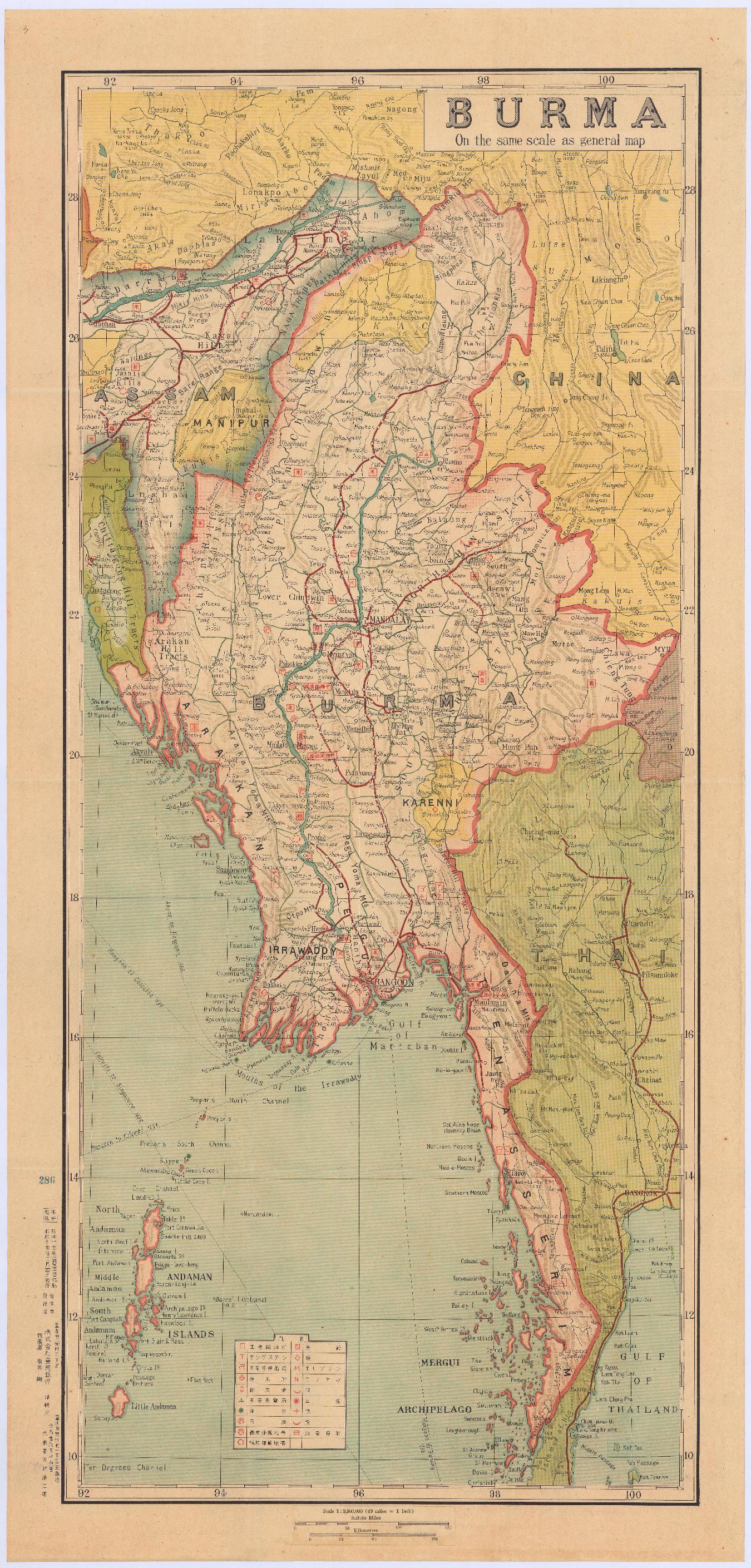

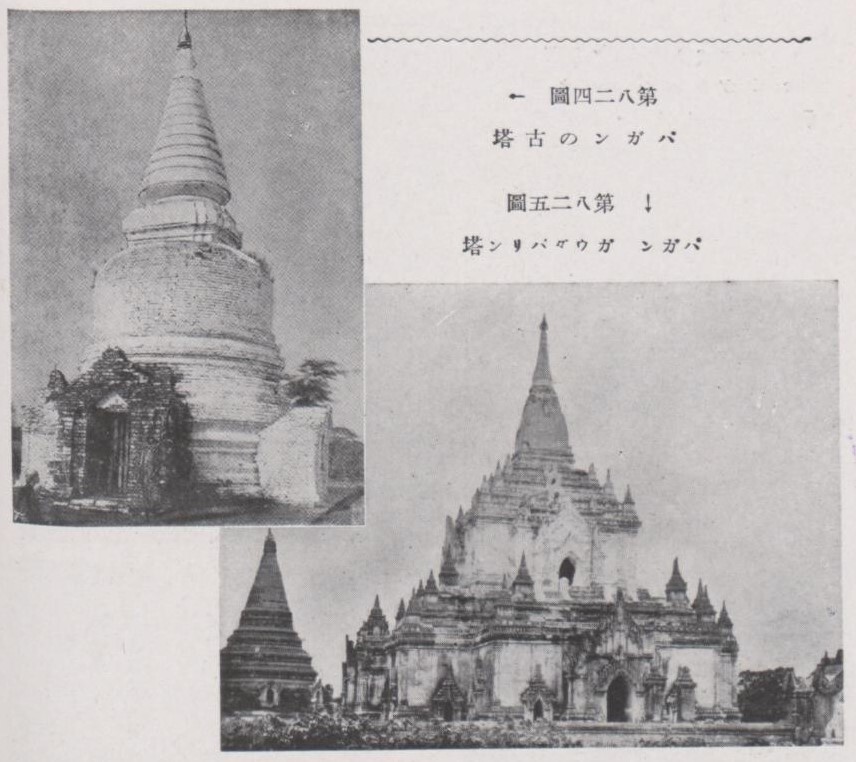

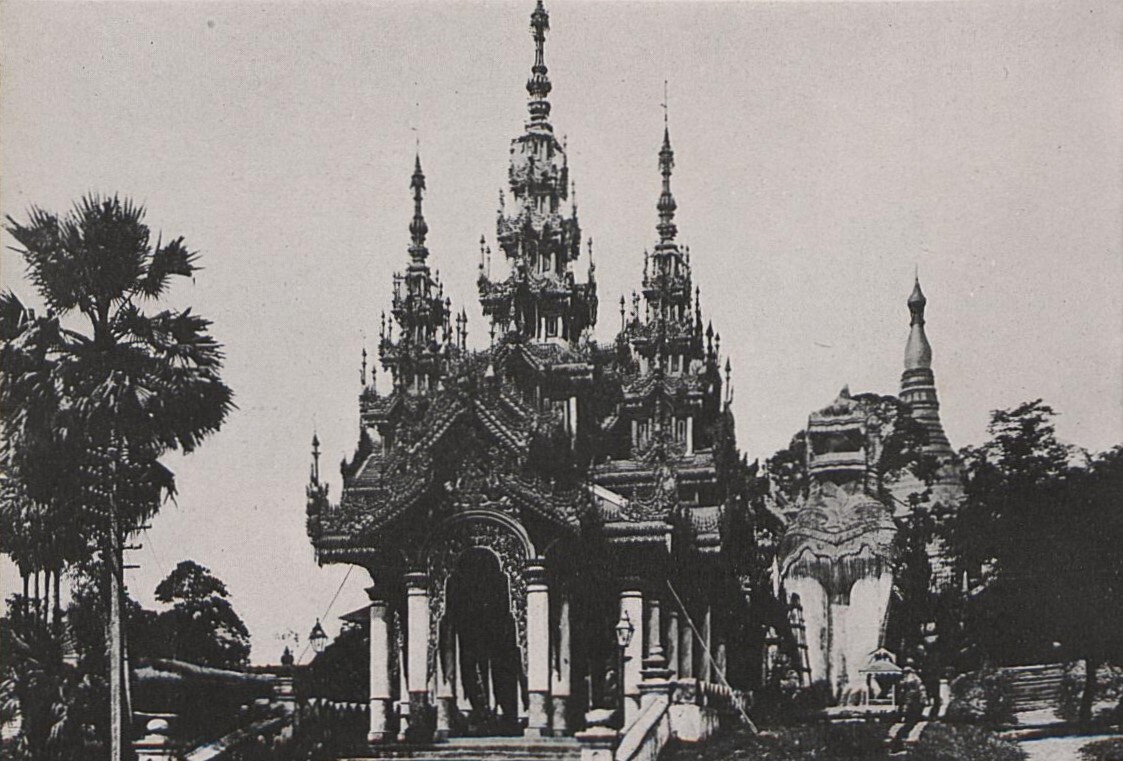

Figure 49: Burma in 1942 Part Two: Buddhist Capital What struck Tung-Lan Chang most about Burma was the extent to which Buddhism thrived in the country and the sheer number of temple constructions. Like Thailand, Burma was a destination of Buddhist pilgrimages. On his way to Rangoon, Tung-Lan Chang once encountered a white tower on the hill which he initially mistook for a lighthouse before coming to the realization that it was in fact a temple or pagoda. Such constructions marked their presence everywhere from the bustling streets to the middle of nowhere. The pagodas of varying sizes from Bagan in central Burma even numbered in their millions. Of the pagodas found in Rangoon, the most famous was the Shwedagon Pagoda, located close to the northern edge of the city. Tung-Lan Chang hired a carriage to travel there and in half an hour reached a temple of constant stream of worshippers. Paying homage to the temple, he took off his shoes and followed a staircase upwards through hundreds of steps and a long gallery to find the carvings and paintings on the patio at the top and more than a dozen of little shops on both sides selling Buddha statues and books. Towards the end of the staircase was the clear view of the Shwedagon Pagoda which was surrounded by dozens of smaller pagodas. The courtyard resembled that of the Senso-ji, with scores of pigeons, stalls trading in pigeon feed and children carrying peas for feeding them.

Figure 50: Pagodas in Bagan, Burma

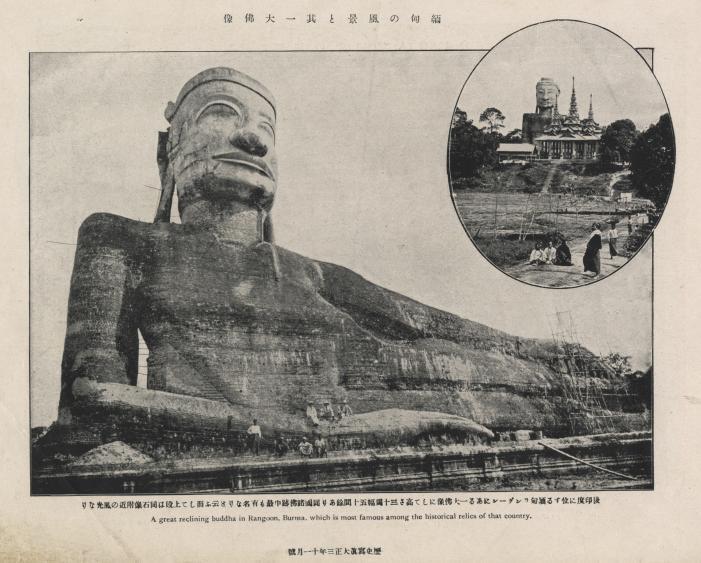

Figure 51: Entrance to Shwedagon Pagoda, Burma Part Three: The Reclining Buddha and Women Tung-Lan Chang raised the issue of increased incidence of nostalgia during encounters with familiar things in a foreign land. An example would be Japanese soldiers’ particular affection for Burmese women whose rounder faces (Figure 53) were taken to be characteristic of Japanese women. After developing some knowledge of the Burmese language, Tung-Lan Chang noted with great surprise and considerable interest that Burmese grammatical structure resembled Japanese. On the other hand, the usual upright sitting posture of the Buddha on the lotus was contrasted with the preponderance of the reclining Buddha in Burma (Figure 52).

Figure 52: Large Buddha Statue in Rangoon, Burma, during Japanese Rule

Figure 53: Burmese Women

Part Four: Monks and Crows Tung-Lan Chang listed monks and crows as two other major features of Burma besides the abundance of pagodas. In Rangoon alone, there were more than 20,000 monks. By seven years of age, boys were sent by their parents to a Buddhist temple studying for at least seven days. Such temple schools (the ponchichon in Burmese) were similar to Japan’s Terakoya, the educational institution for the ordinary people during the Edo Period. The monks served as teachers in these temple schools which later came to be primarily in the service of children from impoverished households. There were no desks or chairs indoors and pupils did their work on the floor. Education in these temples was deemed an instrument for the wider adoption of the official language in Burma. Tung-Lan Chang also witnessed local monks delivering sermons and attending monks in a reclining posture. On inquiry, he learned that it was the respectable posture to assume in front of the elders. The temples schools, in great abundance as the pagodas were, marked themselves out for foreigners with their red and white stripes in bright color as well as their triangular-shaped tiered towers.

Figure 54: Burmese Monk and Pupil

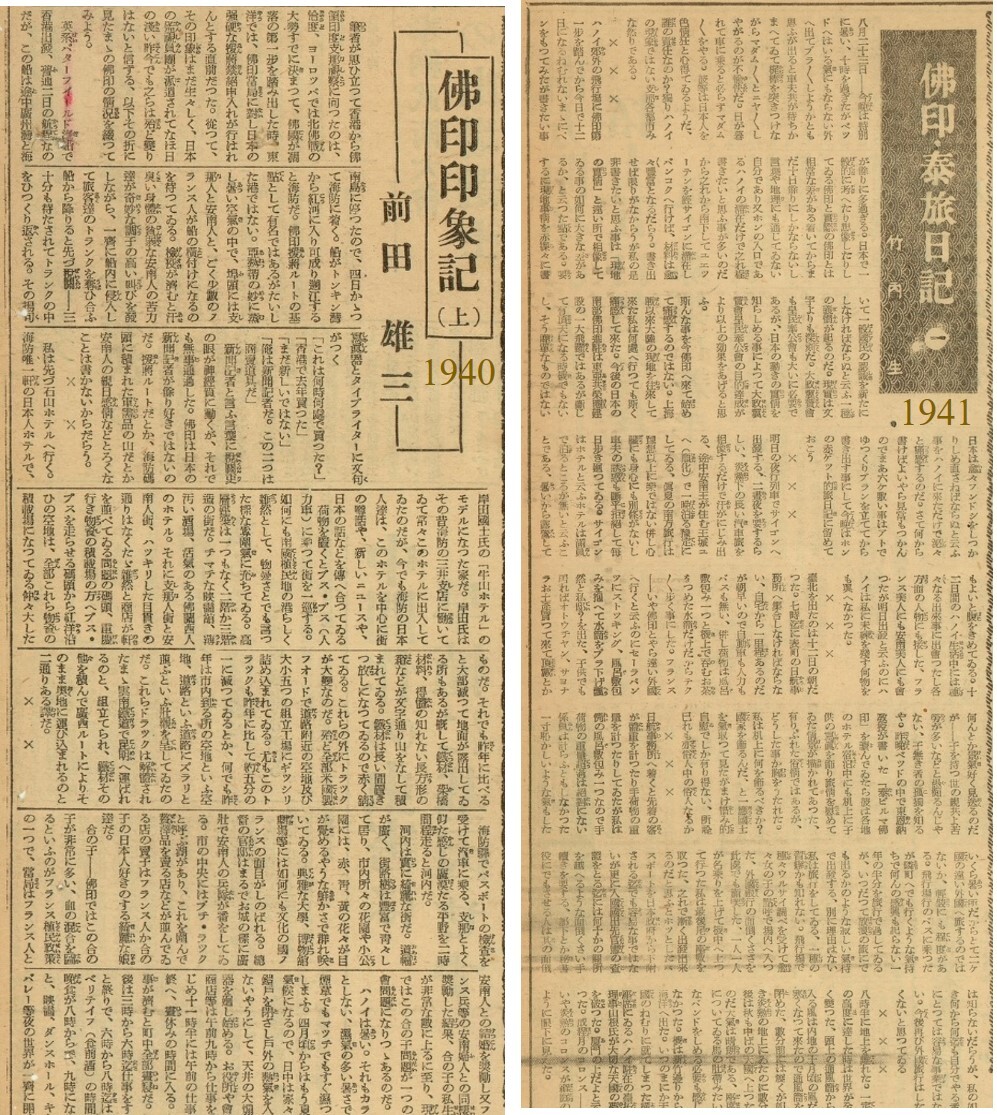

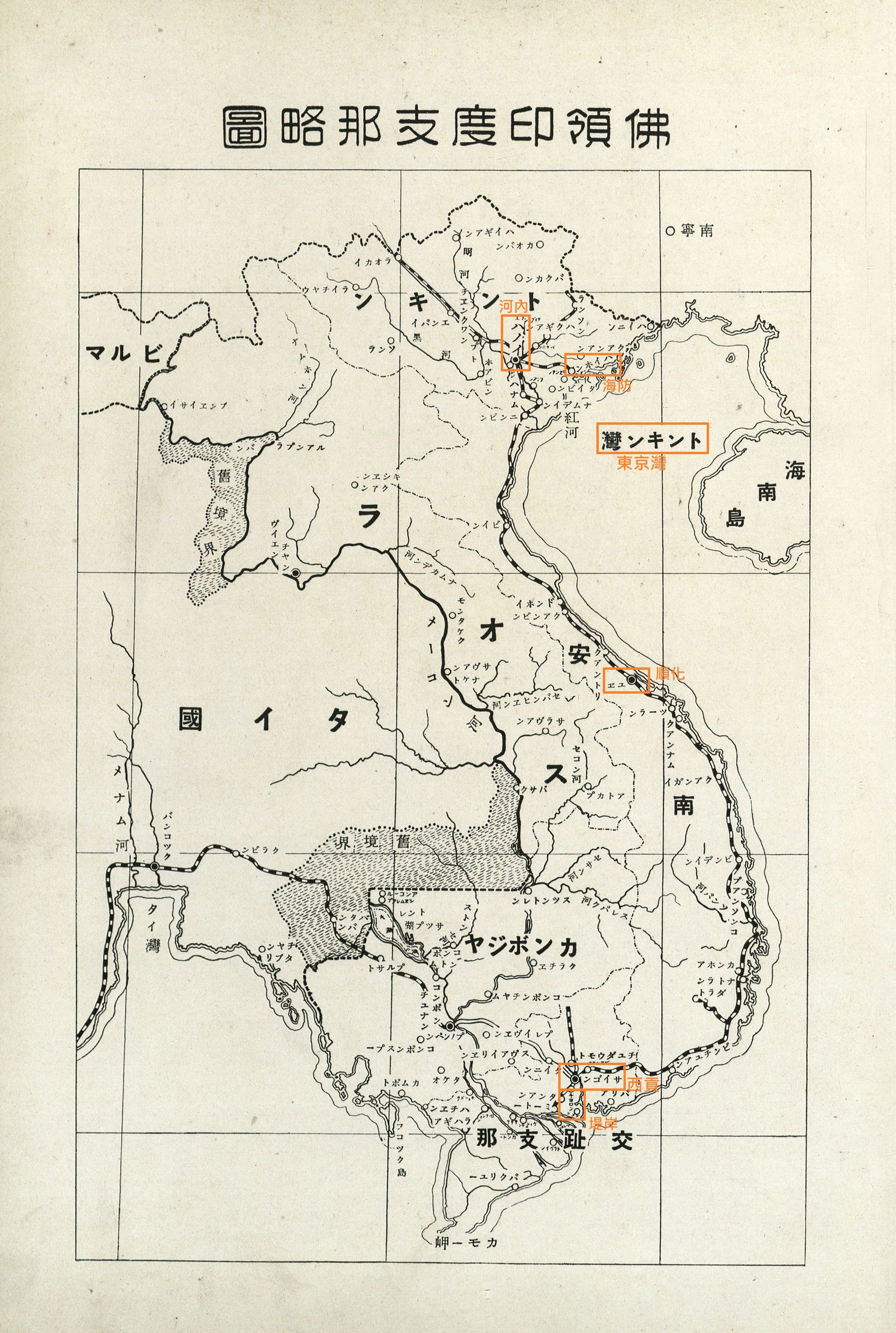

Figure 55: Street View of Rangoon, Burma Part Five: Travel through Indochina, 1940 – 1941 The serialized accounts of travel published in “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” included two concerning Indochina, written respectively by correspondent Yuzo Maeda for his trip to Indochina (French Indochina) in April 1940 and Kiyoshi Takeuchi, the editor of “Taiwan Shin Min Pao”, from August 1941. As the Japanese forces formally made their entry into Indochina in September 1940, the two accounts of travel helped to contrast the situations in Indochina before and after the Japanese occupation. Maeda and Takeuchi took roughly the same routes through their travels in Indochina: both started their trips in Hanoi making for Saigon (Ho Chi Min City today). The two places were separated by 1,600 kilometers by a journey on train that made a stop in the royal city of Hue. Maeda’s account was more detailed, going through local situation, local customs and local background. In contrast, Takeuchi’s account appeared rather incomplete, recorded fewer details and with an excessive focus on the quotidian nature of travel by air in addition to personal feelings.

Figure 56: Accounts of Travel by Yuzo Maeda and Kiyoshi Takeuchi in French Indochina in 1940 – 1941

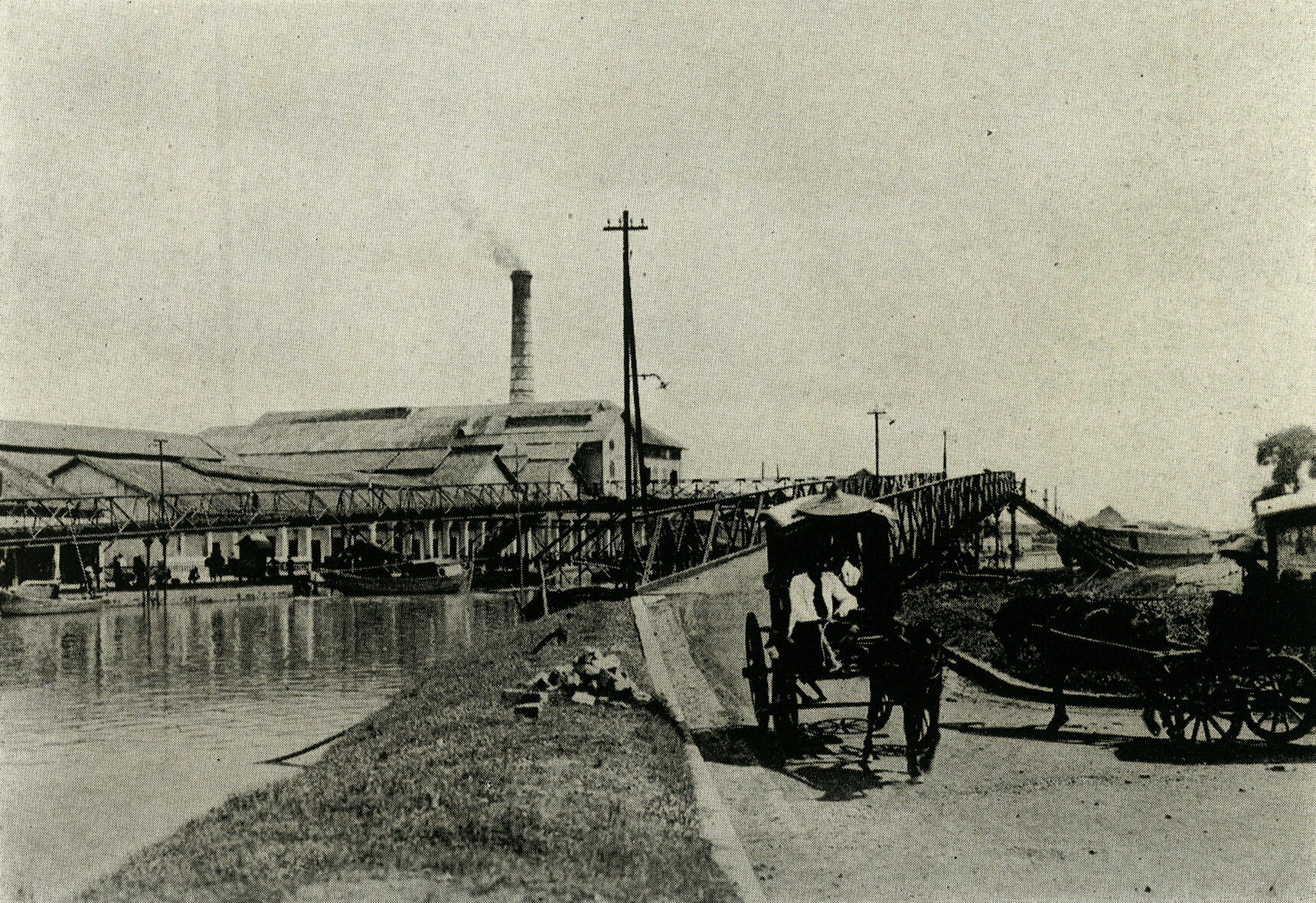

Figure 57: Overview of French Indochina in the 1940s Part Six: Blocking the Route of Aid to Kai-Shek Chiang Yuzo Maeda decided to travel from Hong Kong to French Indochina in 1940 at a time when France was preoccupied with the war in Europe and much distracted from the situation in Nanyang. Locked in a fierce struggle with Japan, China continued to receive supplies like weapons from the United Kingdom and the United States as transported through Hong Kong, the Soviet Union, Burma as well as Indochina. Of these locations of entry, French Indochina was the most important. Supplies were transported from Haiphong in northern Vietnam through the Kunming-Haiphong Railway to Chinese Yunnan. Repeated Japanese bombardments failed to disable this railway. The Japanese finally occupied Hanoi in September 1940, sealing off the region from continued support for China. When Maeda departed for Vietnam from Hong Kong, Japan was already demanding in tough terms of the French Governor of Indochina to stop Chinese access to the aid aforementioned and a monitoring group was sent to French Indochina. As the nexus of the route for aiding Kai-Shek Chiang, the port of Haiphong, where Maeda made the first leg of his itinerary, was not exactly fit for purpose and was crowded with piles of all kinds of supplies destined for Chongqing. These supplies were carried by Ford vehicles of American origin to various nearby factories to be disassembled. The parts were then carried via the Kunming-Haiphong Railway to Kunming to be reassembled and then sent from Guangxi into the Chinese inland.

Figure 58:View of Textile Factories from Port of Haiphong

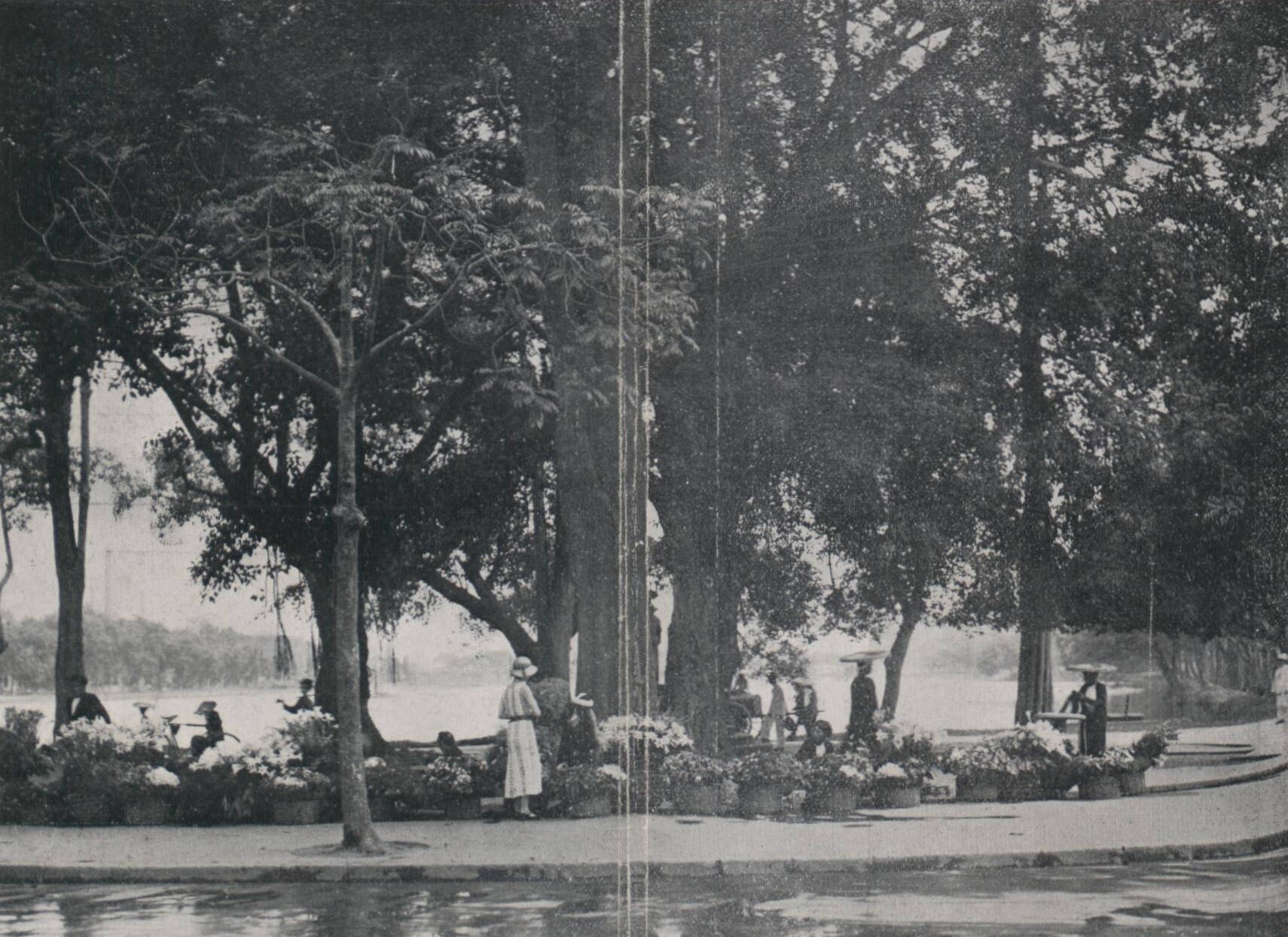

Figure 59: Soldier of Annam in front of the Headquarter of the Japanese Monitoring Group in French Indochina, 1940 Part Seven: Capital in the North – Hanoi Hanoi had been a political, economic and cultural center in northern Vietnam since the 11th century. It was also an ancient capital of Vietnam, with an abundance of historical and cultural legacies and monuments. Yuzo Maeda found Hanoi a very beautiful city where avenues were lined by trees, parks and flowers of all kinds. Universities, museums and theaters were also available. The mansion of the Governor was as large as a castle and Vietnamese sentries stood guard taking shifts. He also discovered in shops Vietnamese women of seemingly interracial or French parentage. French policy encouraged marriages between the French and the Vietnamese and many French soldiers lived with Vietnamese women, resulting in a large number of children of mixed parentage and the attendant social issues. It was also very humid in Hanoi as evidenced in matches and tobacco going bad quite fast. It felt like the summer in April and doors and windows were firmly shut to keep out the hot air while large electric fans on the ceiling stayed in operation. Public institutions and commercial firms ran between 9 and 11:30 am, with a break for nap, and then resumed from 3 to 6 pm. Pre-dinner time was between 6 and 8 pm and dinner did not start until 8 pm. Night life began with theaters, ballrooms and bars (Ikazaya) after 9 pm. Maeda found movie theaters in Hanoi rather small but smoking on a rattan chair while watching movie he still had a good time. Ballrooms and bars were entertainment for the masses, where social etiquette was less observed and dance after drink was the norm with a good time readily at hand.

Figure 60: Governor Mansion of French Indochina

Figure 61: Road Trees and Gardens in Hanoi during the 1940s

Figure 62: Francis Street, Hanoi

Figure 63: Street View of People of Annam in Hanoi in the 1940s

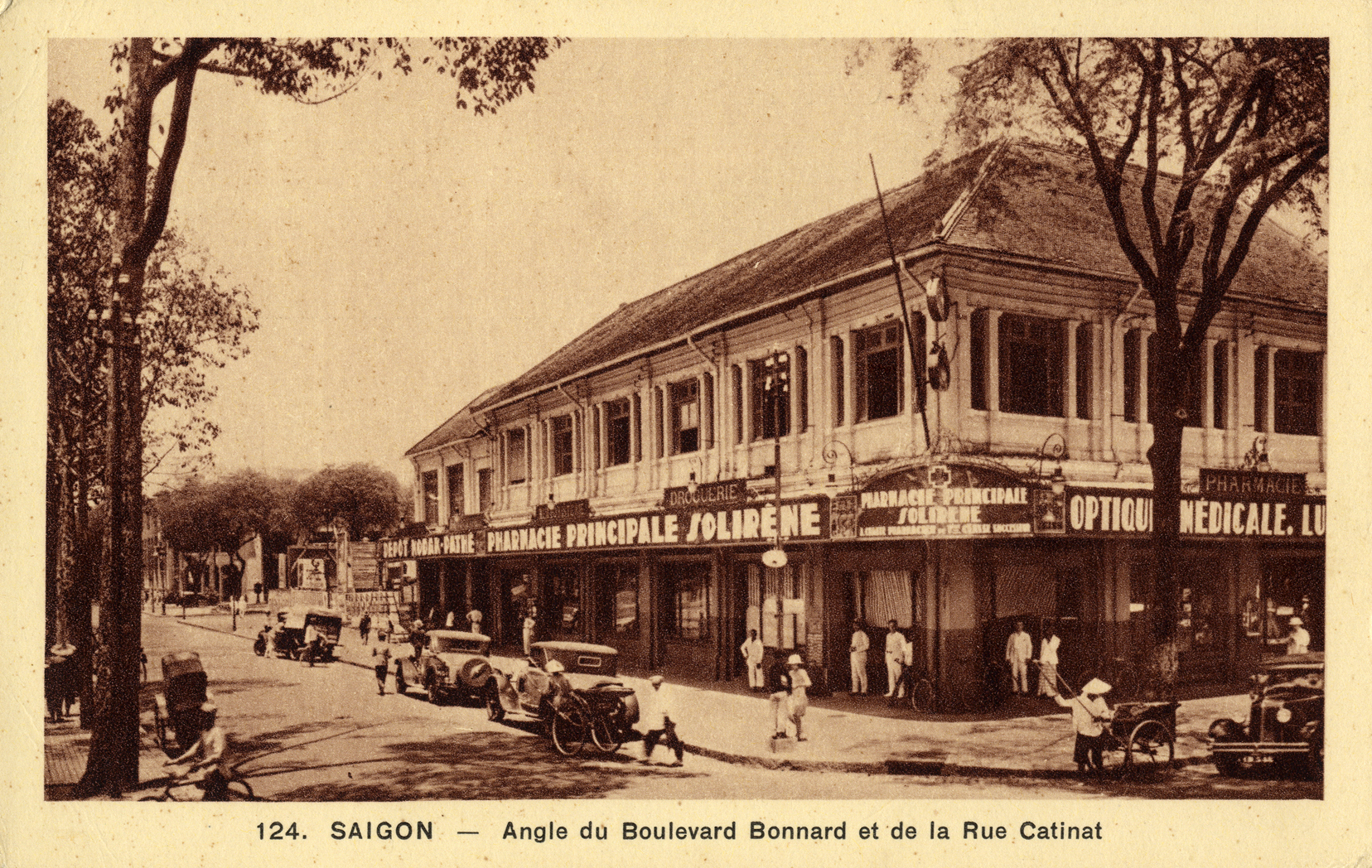

At the conclusion of his trip in Hanoi, he purchased a ticket for second-class sleeper for the train heading for Saigon. With the other three sleepers in the car being taken up three women he was stranger with, he felt quite uncomfortable. Even for a fast train, the journey to Saigon still took two whole days. Furthermore, the further into the south they went the hotter it got. Windows had to be kept wide open with electric fans in operation all day long. If the heat remained intolerable, refreshments in the dining car would be a last resort. After a journey through the coconut trees and rubber trees, the train finally reached Saigon at 3 pm on the third day. Blinding sunlight in tropical Saigon was quite different from what was the norm in the subtropical north. A check on the passport at the train station was followed a shower in the hotel which did not allow for a bath – much to the frustration of Maeda. He was able to fall asleep after four showers in total that day and only with electric fans on. The dining hall was much in the fashion of a seaside resort, with both men and women in shorts or bright-colored garments which was full of tropical feel. The main avenue in Saigon took after the European style, orderly and neat. It turned out to be about the only attraction in Saigon whereas the whole of the cityscape in Hanoi boasted such attraction.

Figure 64: Street View of Saigon

Figure 65: Boulevard in Saigon

Figure 66: Kachina Street, Saigon Part Nine: In the Streets of Chinese Community – The Embankment During his time in Saigon, Maeda also took time to visit the adjacent embankment, a city about 15 minutes away from Saigon by a rickshaw. The Embankment was a community of Chinese immigrants, housing 500,000 of the 600,000 Chinese residents in Vietnam. The local Chinese mainly ran a business in rice grain. The sheer traffic of boats carrying the grain on the Canal of Saigon, and the robust economic potential it suggested of the Chinese people, much impressed Maeda. The street view on the Embankment was thoroughly Chinese, without a shred of European architecture. The ongoing Japanese invasion of China might have led to the incident in which Maeda, photographing on the street, had a brush with a profanity-spewing, glowering Chinese crowd that even spat at the feet of Maeda.

Figure 67: Boats Trading in Rice Grain on the Embankment

Figure 68: Canal on the Embankment in the 1940s

Figure 69: Grain-carrying Boats on the Canal of the Embankment in the 1940s

Figure 70: Grain Refinement Factory on the Embankment

Figure 71: Cholon, China Town on the Embankment

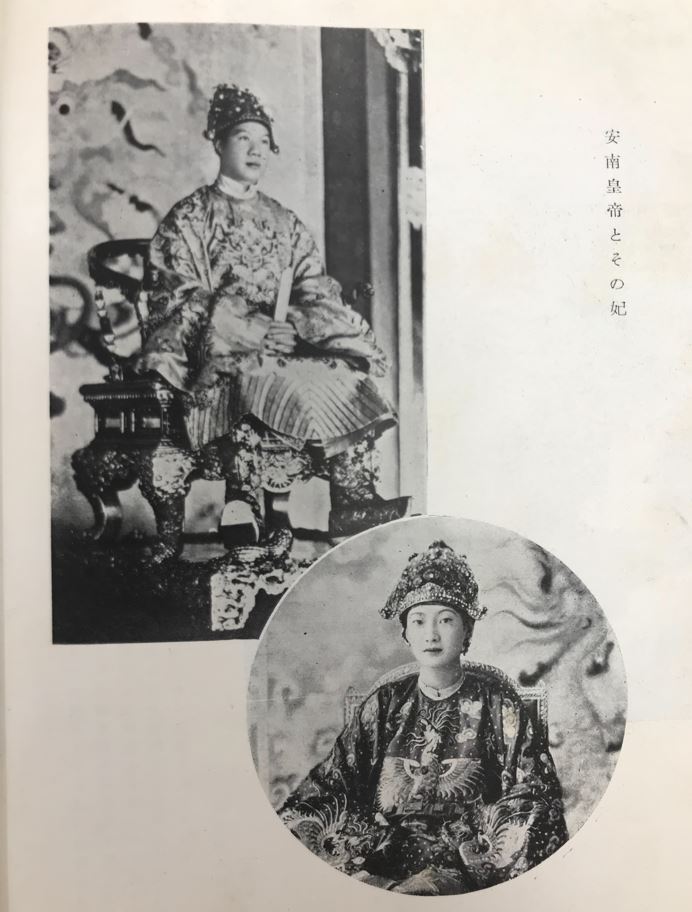

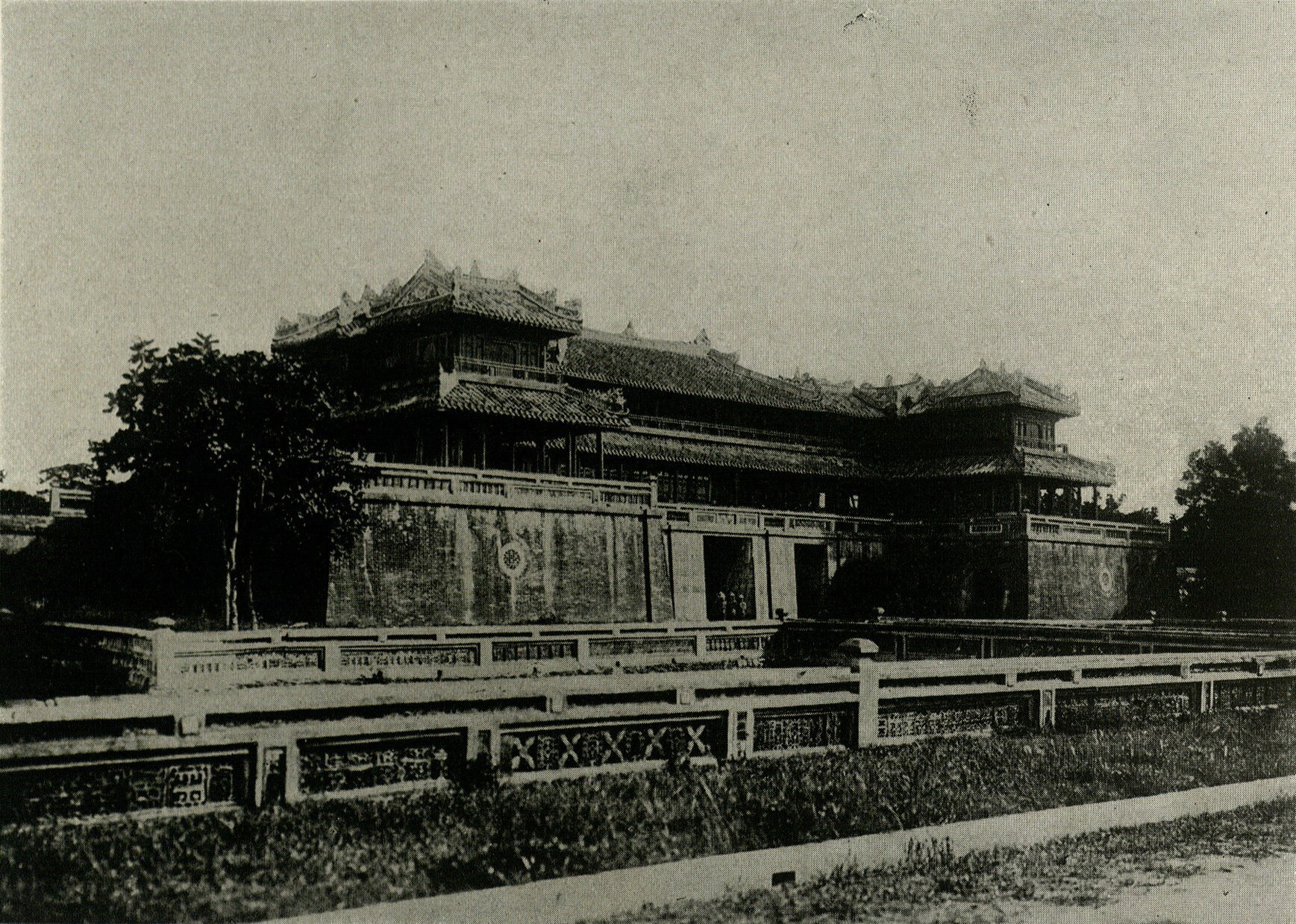

Figure 72: Grain-carrying Boat on the Embankment in the 1940s Part Ten: Royal Capital of Vietnam – Hue On his journey back to Hanoi from Saigon, Maeda also made Hue, the capital of Annam, part of his itinerary. While Haiphong, Hanoi and Saigon were Europeanized cities, Hue stood out as one that was purely Vietnamese. Maeda explored the perimeter of the royal city and found mostly empty, quiet streets lined by houses made of yellow clay. Few ships sailed on the Perfume River through Hue. The streets were imbued with tranquility in an otherwise lifeless city. But by the night, ships resembling exquisitely decorated Chinese cruises run by songstresses were active. Farther afield into the outskirts lay the old royal city. Here, the Chinese cultural influence was strong, with the style of the Ming Dynasty much on display. Amidst the somber songs of the songstresses, Maeda sighed: “The tragedy of the ancient Annam – what a pity!” Maeda briefly went through the situation of Bao Dai, the Vietnamese king of Annam, who was a youth of 25 years of age, was educated in France, loved sports especially galloping on horseback and had a queen two years to his junior. She was the daughter of a wealthy Vietnamese man and known for being a great beauty in characteristically Vietnamese way. King Bao Dai of Annam had at his disposal a force of 200-men strong from the army but they were more of servants at the door than guards for the royal city. The king had nothing but the city itself, without any power or prestige, and was a mere figurehead for the Governor of French Indochina. Towards the end of his account, Maeda made mention of the presence of a certain type of natives around the royal city who traded fur for food. According to local reports, these people moved in a group of ten, with long hair and naked torso. They looked like women from afar but fierce-looking men when nearer. It was also alleged that they consumed the remains of dead relatives, in keeping with a cannibalistic tradition.

Figure 73: Emperor Bao Dai of Vietnam and Consort Nam Phuong

Figure 74: Royal Palace in Hue

Figure 75: Mountainous Aboriginal Men in French Indochina in the 1940s Part 11: Pro-Japanese Sentiment With his itinerary ending in Hue, Maeda was back in Hanoi, which was known as the “Paris of the Orient”, where tasty French cuisine and wine and young girls were readily available. Maeda gasped at the aimless, indolent lives the youth of Vietnam led, dancing the Waltz day after day. He thought that the fortunes of the Vietnamese people would only take a turn for the better once the French were driven out by the Japanese. He felt great affection with the Vietnamese people, regarding them as the little brothers of the Japanese, without a hint of domination and competition in their spirit, a fact that he attributed to prolonged French rule that sapped the country of any initiative and fostered a desire for the status quo and leisure. Meanwhile, he observed that the Vietnamese people held the Japanese in extreme admiration and a pro-Japanese stance was in vogue. And Japanese travelers in Vietnam could feel it: people were always inquiring about Japan, be it the personnel on the train and in the hotel or shopkeepers. Maeda thought that the Vietnamese people’s attitude towards Japan was better defined by blind faith in a would-be savior than mere respect. With the meager presence of only around 250 Japanese people in Vietnam and the French authorities banning researches on and books about Japan, the Vietnamese people must have been quite ignorant of Japan as a nation. And yet, they were cognizant of the war between Japan and China as well as Japanese military progress in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Hankou and Guangdong and even the fact that it had closed in on Guangxi. Maeda believed that the reason behind the pro-Japanese sentiment in Vietnam was none other than hero-worshipping in the wake of military success. From a broader historical perspective, the Vietnamese people loathed China for its long oppression and the economic and commercial domination by Chinese immigrants. Long-standing French obscurantism and exploitation added to the insult. In the mind of the Vietnamese people, Japan emerged as a new power capable of overcoming a country as large as China and the only nation likely to sweep away the status quo for Vietnam. Furthermore, the Japanese, perceived as a cultured nation and a fellow Oriental people in Vietnam, were thought more positively than European people of completely different values. As Maeda envisioned, a little more than a month later in September 1940 the Japanese forces began moving into French Indochina and reached Saigon in July next year, in effect placing French Indochina under Japanese control. The Nazi-backed Vichy France had lost practical powers in the region. When Takeuchi Kiyoto made his trip to Indochina in 1941, it had fallen under Japanese occupation. He talked about how only after setting foot in French Indochina did he realize that there was such a large gap between his expectations and the reality of the land, writing that Japanese occupation of French Indochina, though a huge step for the development of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, was no ground for contentment and that Japan ought to be even more vigilant and muster its strength for there was more to come.

Figure 76: Residents of Hanoi with Japanese Soldiers in the 1940s |

|