|

With the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the European Theater of the WWII began. In 1940, Japan officially aligned itself with Italy and Germany, forming the Axis Alliance. The attack on Pearl Harbor towards the end of 1941 triggered the Pacific Theater of the war, making the prolonged armed confrontation between the Axis Powers and the Allies – consisted mainly of the Republic of China, the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union – more explicit. Travelers stepping into Europe and the United States felt the wartime tension, walking the fine line between hostility and friendliness. “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” published four serialized accounts of travel to Europe and the United States, including feminist Waka Yamada’s visit to the United States meant to build friendship, Tomio Takeda’s tour of the film industry in Los Angeles, painter Ikuma Arishima’s trip to Hawai and educator Yayoi Yoshioka’s travel through a destabilized Europe. Their accounts brought to light the conflicting perceptions in Europe and the United States shrouded in wartime. This piece focuses on the experiences of the two women aforementioned during their stay on the two sides of the Atlantic.

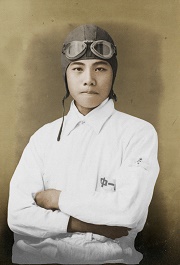

In October 1937, Waka Yamada visited the United States as an Ambassador of Friendship and a representative of Japanese women, dividing her time primarily between Los Angeles and San Francisco on the west coast before traveling to Washington D. C. After a tour of more than four months, she returned to Japan in March 1938 and composed “Pilgrimage to the United States”, which was published by “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” in two chapters on 19 March 1938, documenting her thoughts on the American tour. Waka Yamada (1879 – 1957) was a Japanese feminist and sociologist. Sold into prostitution to the United States in 1879, she extricated herself from her plight and started doing translation work for the Presbyterian Church. In 1903, she returned to Japan with her husband Kakichi Yamada. Inspired by Swedish feminist Elle Key (1849 – 1926), she began striving for rights for women, advocating that the state ought to offer protection for women as wife and mother. She campaigned for a “Maternal and Child Protection Act” and founded the Maternity Protection League. After the WWII, she also established schools to help prostituted women earn a living and escape poverty.

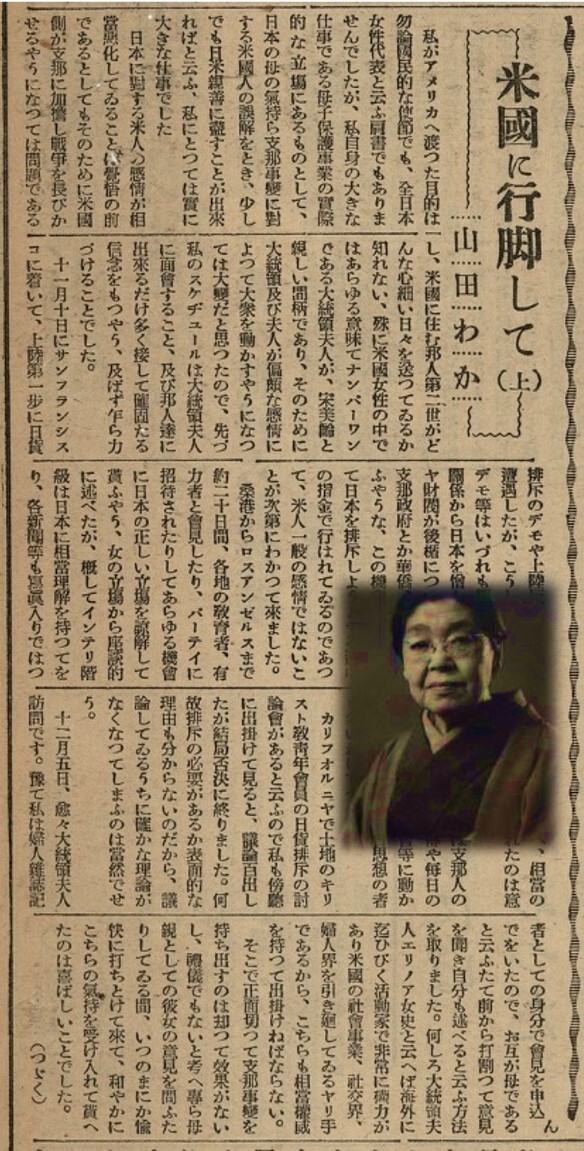

Figure 33: Yamada’s “Pilgrimage to the United States”

Part Two: Anti-Japanese Sentiment Yamada arrived in Los Angeles on 10 November 1937, at a time when the Japanese were precipitating the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and commencing their invasion of China. With the rapid fall of the northern part of the country, China requested diplomatic support of the United States. As part of the effort, Shih Hu, for one, delivered his speeches in the United States in a private capacity. The campaign from multiple fronts worked through the Chinese expatriates in the United States and a boycott of Japanese goods was unleashed amidst a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment. Yamada recounted her encounter upon arrival with a demonstration against Japanese goods and protestation at their reaching American soil. On the belief that these did not reflect the real view of the masses in the United States, she thought that these anti-Japanese actions all had an economic dimension, that they were backed by wealthy Jews who loathed Japan and that the Chinese government and expatriates took the opportunity to plot against Japan. With the Japanese invasion of China escalating, Chengting Wang, the Chinese ambassador to the United States, had an audience with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1938 requesting for assistance. He was told that the occasion was not ripe for concrete action due to the prevailing desire for neutrality in the Congress of the United States but it was intimated that banks would not be able to loan to Japan and that the seizure of the assets of Japanese citizens in the United States was being discussed.

Figure 34: Scene of Japanese Military Band Entering Nanjing after Its Fall in December 1937

Figure 35: Telegraph from Chengting Wang, the Chinese Ambassador to the United States, of the American Response to the Request for Assistance against Invasion

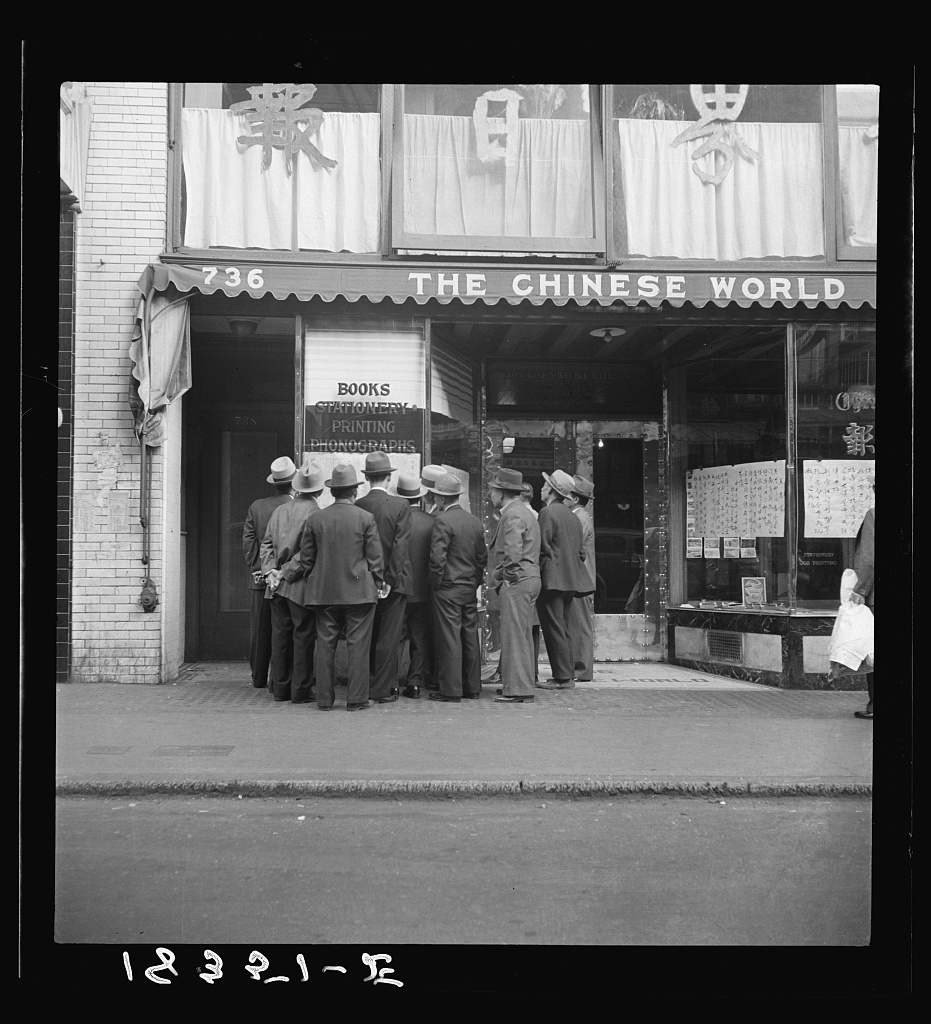

Figure 36: Chinese Expatriates in San Francisco Reading about the Fall of Guangdong outside the Publishing House of World Journal

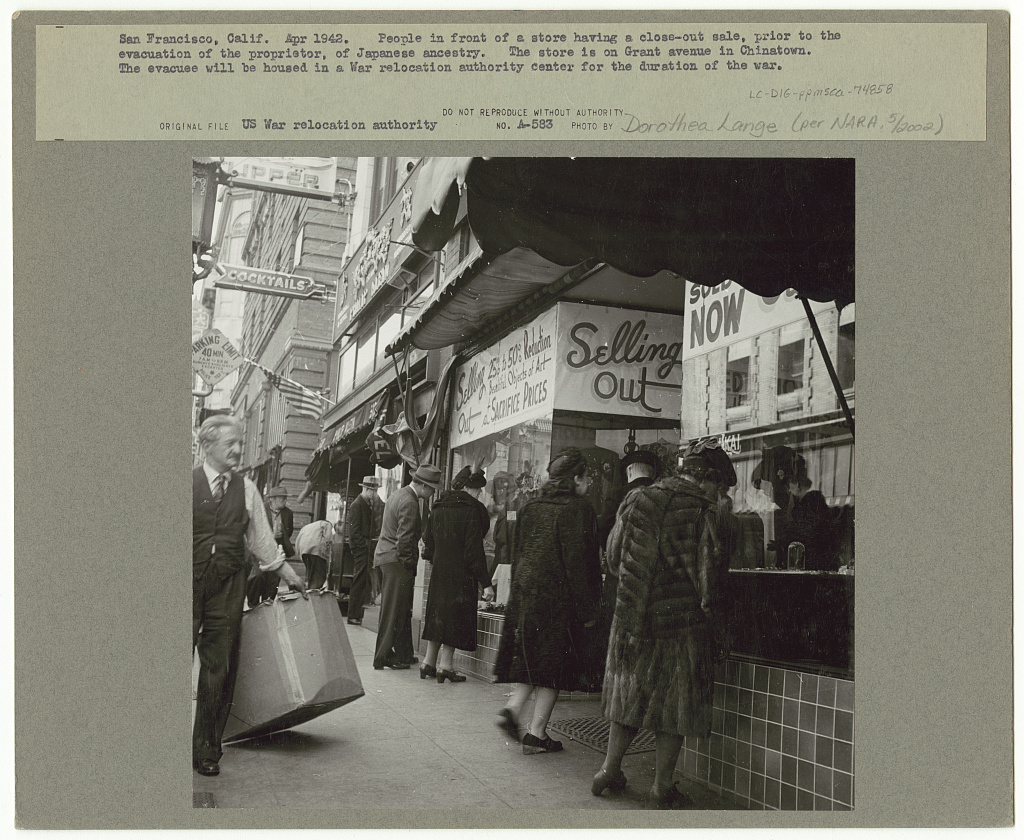

Figure 37: Japanese-owned Shop in San Francisco Forced to End Operation and Hold Final Sales

Figure 38: Anti-Japanese Slogan on the Streets of San Francisco during the WWII, 1942 Part Three: Meeting the First Lady of the United States in Washington D. C. An important aspect of Yamada’s tour in the United States was meeting with Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady of the United States. It was because the First Lady of the United States was friends with Soong Mei-ling, the First Lady of China, and capable of influencing public opinion on the matter. Yamada’s foremost task was thus to secure an audience with the First Lady of the United States, besides meeting other Japanese figures in the country. On 5 December, Yamada, in her capacity as a correspondent for Women’s Magazine, met with the first lady, who enjoyed great stature and was highly influential with charities and women in the United States, a situation that Yamada felt she had to match with her own professional prowess. The two interlocutors did not broach the Marco Polo Bridge Incident from that July (which the Japanese referred to as the China Incident) and the discussion revolved around the question of maternity.

Figure 39: Photograph of Waka Waka (middle) Meeting the First Lady of the United States in Washington D. C., 1937

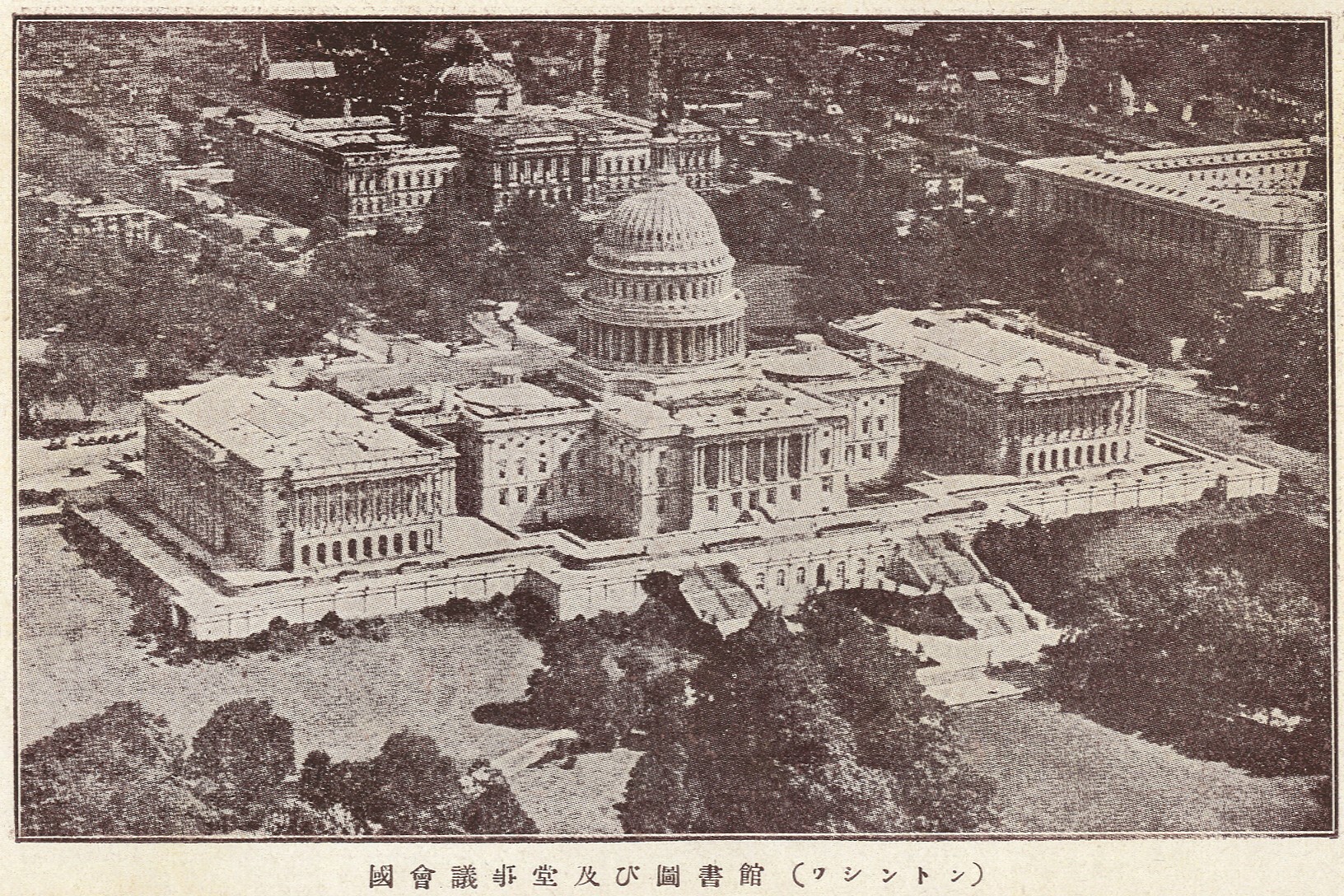

Figure 40: Landmark in Washington D. C. – The United States Capitol Part Four: Publicity of Justification for Japanese Imperialism During the four months of her stay in the midst of geopolitical volatility, she took part in meetings and answered invitations, including those from the west coast and Hawaii, and, taking as many opportunities as possible to socialize Japanese residents in the United States, she came to recognize the deep patriotism of Japanese expatriates. However, Yamada thought that while some Japanese immigrants felt a profound connection with Japan and shared the experiences of the Russo-Japanese War, they could not quite account for their support for Japan’s war. When questioned by Americans for Japan’s reasons for starting war, the second generation of Japanese Americans, who did not understand or speak Japanese, were even more at a loss. Yamada therefore defined her trip as an effort, from the perspective of a woman, to explain the position of Japan’s imperial expansion and hoped to use the occasion to send her messages to the Japanese residents in the United States and their next generation. Yamada expressed her view that generally speaking American intellectuals were able to appreciate the Japanese position but the masses were more influenced by the instigation of Chinese propaganda in the form of protests and speeches and more likely to be anti-Japanese. She attributed this to various vicious means of Chinese propaganda meant to vilify Japan. She believed that Japan need not resort to similarly crude methods and instead should communicate to the United States Japan’s condition in a civilized and elegant manner. Yamada’s observation extended to other aspects of Japanese Americans, including the pain of second generation of Japanese Americans’ inability to become American citizens as bound by the Immigration Laws. On this, Yamada drew the analogy of men and women, who were unequal in most respects, but young and intelligent women were not necessarily at a disadvantage when compared with men. As the argument goes, with different facial features and skin color, the Japanese could not be the equivalent of Americans. Instead of making a comparison, she found it more relevant to become an excellent Japanese individual who revered the Japanese spirit and family tradition, practiced filial piety and earned respect by way of Japanese virtues. With conviction, life was carried by dignity and unsullied by scorn.

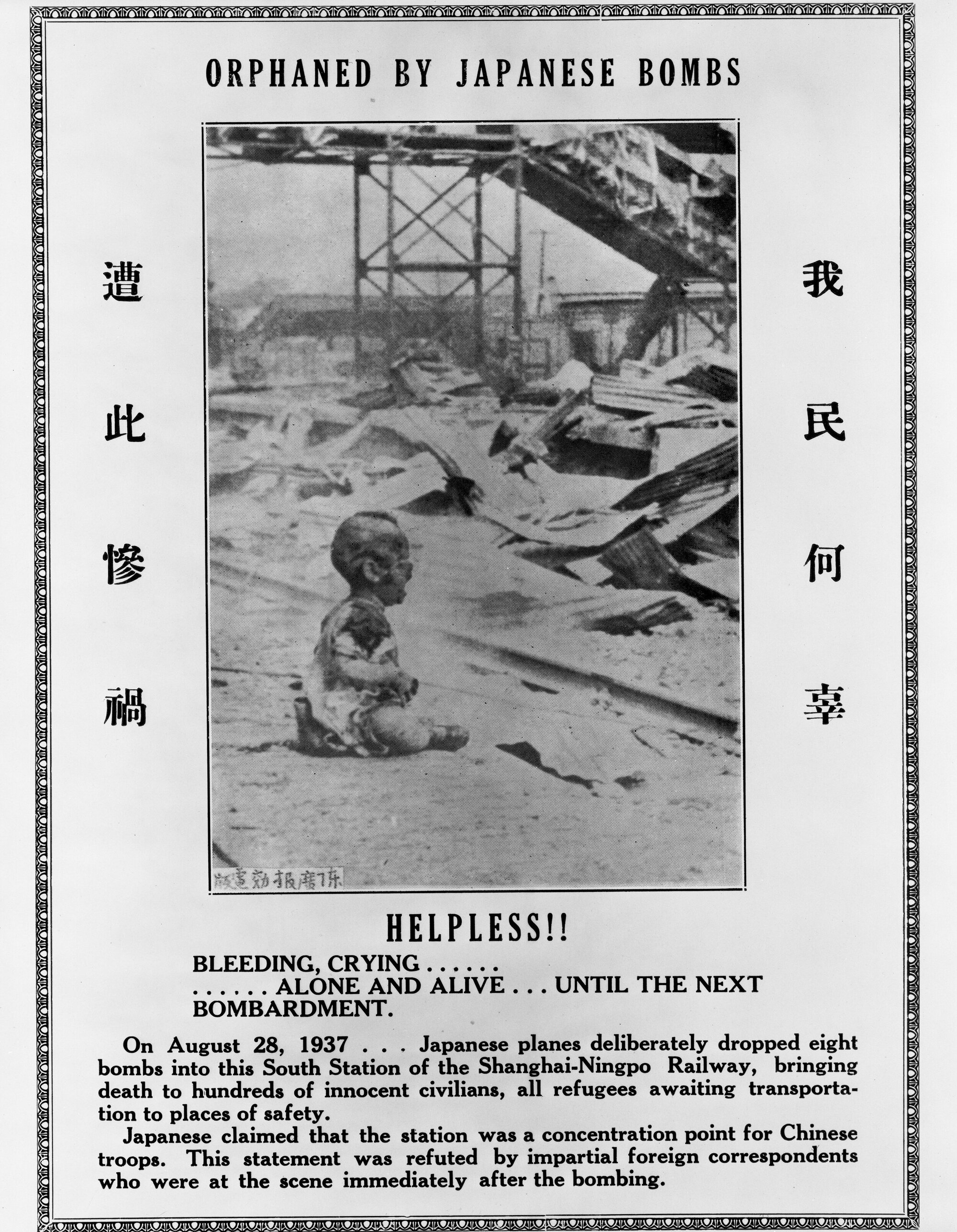

Figure 41: Fund-raising Chinese Poster (Child in Wartime Shanghai in August 1937) Part Five: Yayoi Yoshioka Visited Europe, 1939 Yayoi Yoshioka was a Japanese educator, physician and founder of the Tokyo Women’s Medical School (the Tokyo Women’s Medical University today), dedicating her life to the training of women doctors and the promotion of medical education and research. Ah-Hsin Tsai, the first woman doctor from Taiwan trained in modern medicine, was an alumnus of the said school. During the WWII, Yoshioka served as the first female member on the National Policy Committee, a councilor of the Patriotic Women’s Association, the leader of Greater Japan Union Women’s Youth, an adviser to the Greater Japan Women’s Association and other important positions, guiding the mobilization of youth and women for the war effort. On the eve of the outbreak of the war in Europe in July 1939, Yoshioka was invited to participate in a tour of Europe and her experiences were published in two articles by “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” in November 1939, detailing the local situation before the imminent German invasion of Poland.

Figure 42: Yayoi Yoshioka’s Visit to Europe

Figure 43: Patriotic Women’s Association Praying for Military Success Part Six: Trip Interrupted by the Beginning of War In July 1939, Yayoi Yoshioka traveled to Germany, mainly at the invitation of the National Socialist Women’s League. Finding no sign of the imminent war, she had a meeting with Gertrud Emma Scholtz-Klink, the leader of the League of German Girls and the National Women’s League, and was warmly received. The trip was originally scheduled to participate in the annual rally at Nuremberg in September before departing for Belgium for World Conference on Family Education and then on to Britain and France. Unfortunately, the planned itinerary came to a halt with the outbreak of the war. In August 1939, Yoshioka traveled to Scandinavia (Sweden and Norway in northern Europe) before making her way to Gdańsk, Poland. Even at the time, Yoshioka could discern the encroaching Nazification of the city as if it was about to fall under German occupation. What surprised Yoshioka the most was the news of the signing of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact on her return to Berlin in August. She found the rapidly evolving international situation difficult to come to terms with. And yet, under the extreme censorship imposed by the German government, the general public had no inkling of the shifts in international conditions and discussion of the potential impact of this event on Japan was utterly absent in the press too. Yoshioka was able to glean some information from the Japanese Embassy and a small number of individuals in the press.

Figure 44: Signing of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact in August 1939

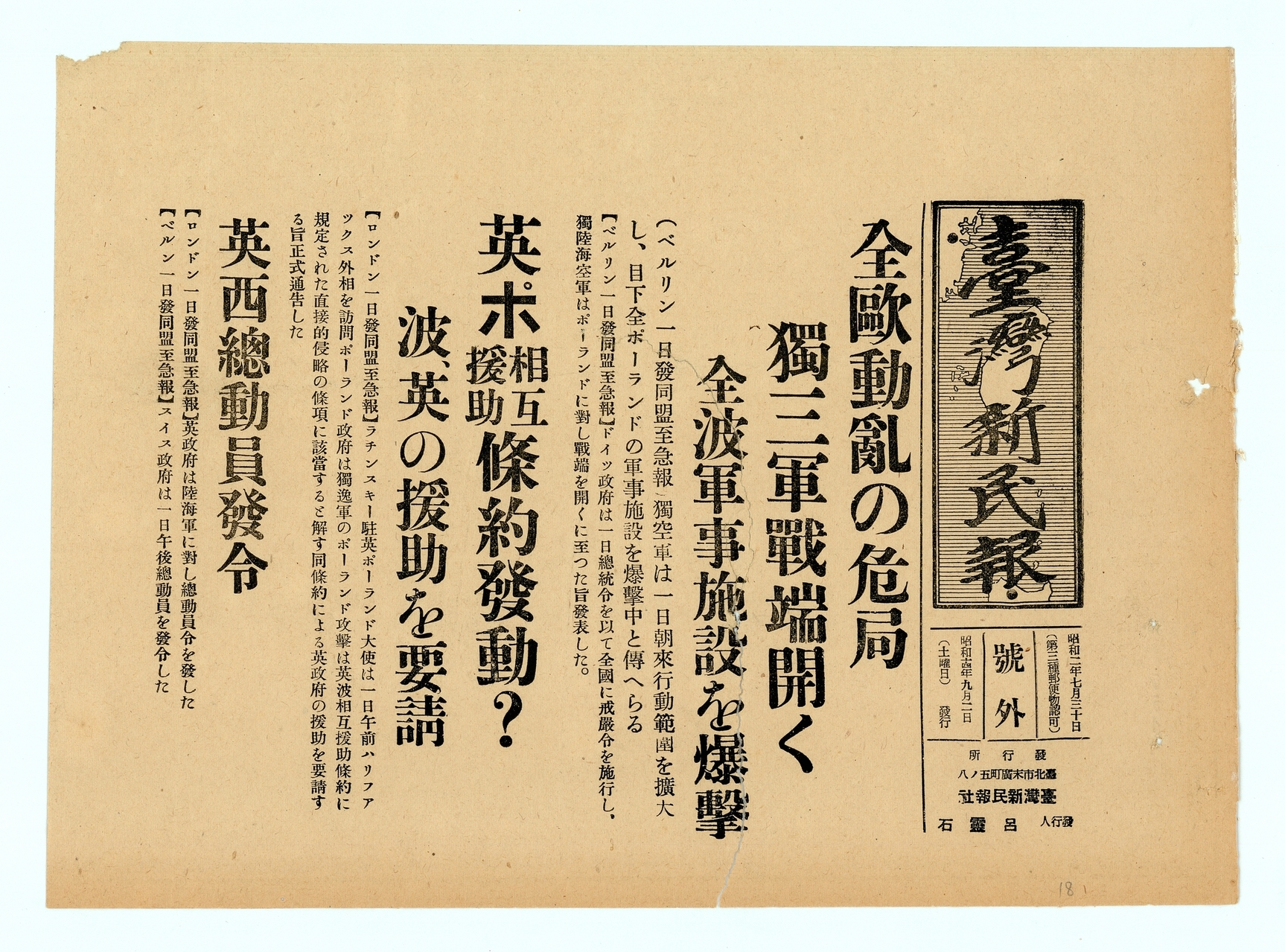

Figure 45: Taiwan Shin Min Pao Reporting the German Invasion of Poland as Breaking News in September 1939 Part Seven: Silence and Fanaticism As a result of the German invasion of Poland, Yoshioka’s planned meetings and trips all fell through under the circumstances. By late August, Yoshioka received an emergency call asking her to immediately return Japan by a ship in Hamburg. But she believed that, as a citizen of a neutral state in Germany, so long as she could stay in Germany she should carry on the task of the German-Japanese exchanges for women to completion. Amidst the broadening of the war, Yoshioka finally departed in the middle of the night on 22 November, taking a detour around Iceland avoid areas of military activity before making for New York. After a voyage of 11 days, she reached New York where she was to be in transit to Yokohama. Of the many repatriated Japanese on the ship, she was the only woman. Yoshioka in her account mentioned the rule of extreme censorship in Germany, keeping the general public totally in the dark about developments abroad. Economic control was also in place, with tight regulation of the provisions and the forbidding of stockpiling or any move contrary to the policy enacted. From a loaf of bread to a piece of cream to a grain of sugar and to a bar of soap, nothing escaped the stringent regulation and there was no access to these things without ration coupons. But the German people seemed amenable to the severe method of governance, choosing to actively ignore things and placing complete trust in Hitler. German women were mobilized as well when the war began and, according to ability, assigned to tasks like typewriting, laundry, machine operating, sewing, cooking, nursing, medical care and more. Yoshioka faithfully recorded the contrast in the local conditions before and after the war began as well as the position of the Japanese in all of this. As she feared, the world was marching unstoppably towards world war.

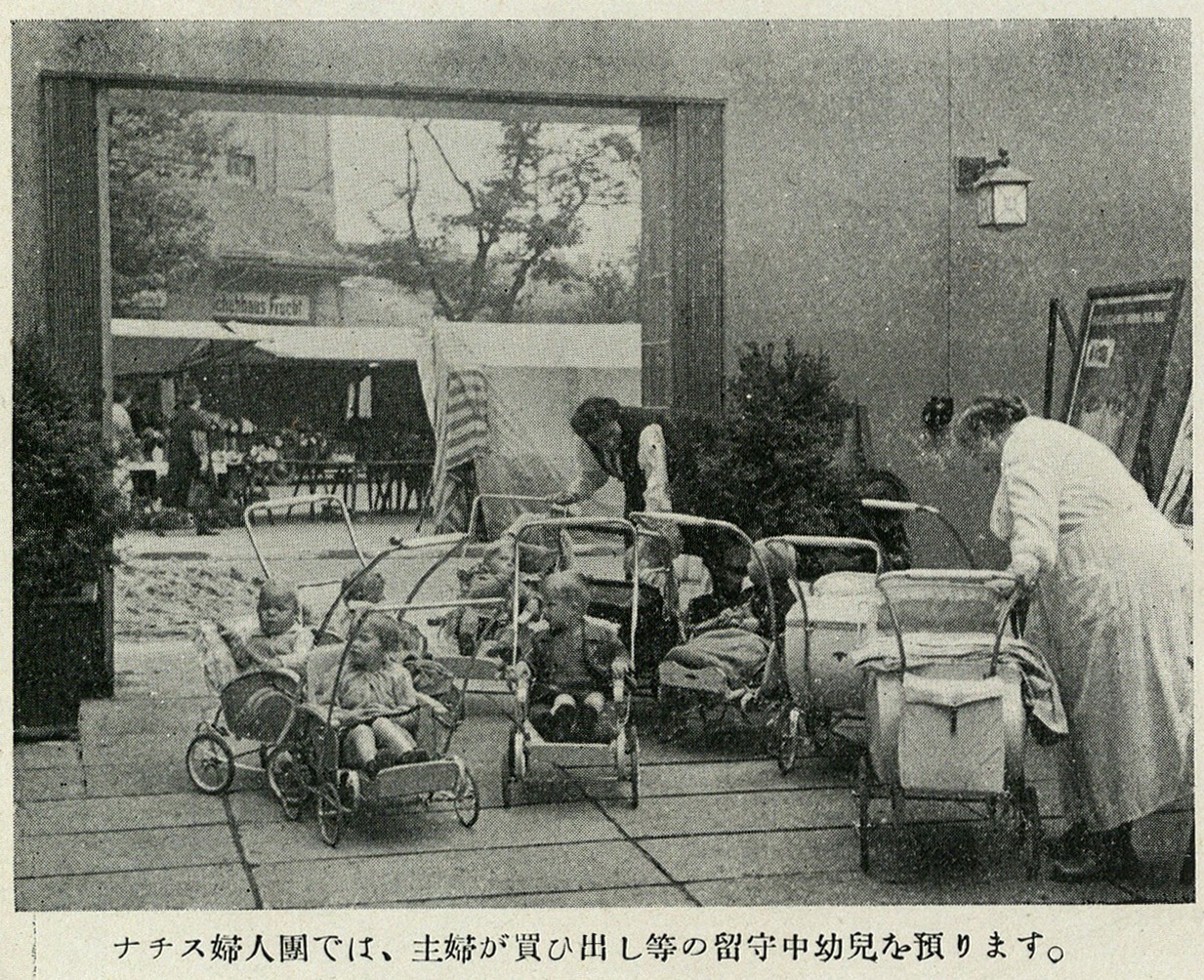

Figure 46: National Socialist Women’s League in Childrearing

Figure 47: League of German Girls |

|