|

The conventional idea that a woman should “obey her father before marriage, her husband during married life, and her sons in widowhood” reveals how Taiwanese women’s existence was dependent on men in the traditional society. Unlike the male heirs who bear the duty of carrying on the family line, unmarried women were often sold as commodities and became others’ adopted daughters, child brides, indentured servants, or even prostitutes during economic hardships.  A Wedding Photo of Lin Zushou and Tsai Jiaoxia, April 27, 1912. A Wedding Photo of Lin Zushou and Tsai Jiaoxia, April 27, 1912. The four young girls and the two women standing beside the newlywed couple were the accompanying maids who would take care of the bride's daily life in the future.

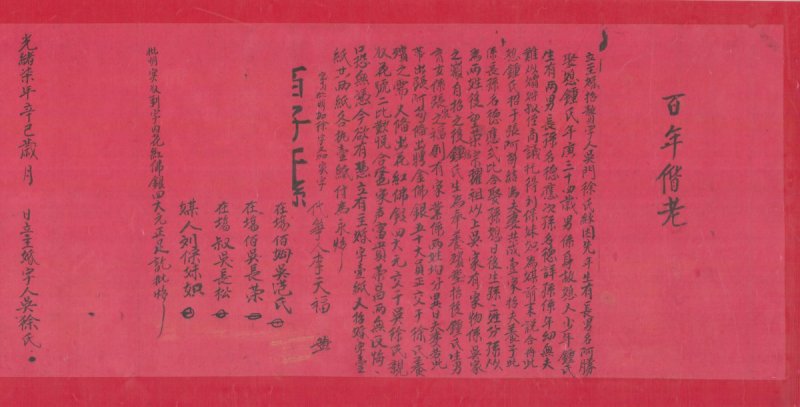

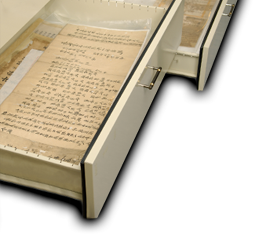

Even after becoming wives, Taiwanese women still had no personal autonomy. Even in instances where the husband died, leaving the women behind, his family’s elders would sometimes choose to adopt another man into the family to serve as the widow’s new husband, who would accept the responsibility of raising the children or carrying on the family line.  An uxorilocal marriage agreement by Mrs. Wu (née Xu), 1881. An uxorilocal marriage agreement by Mrs. Wu (née Xu), 1881. When Mrs. Wu’s eldest son passed away, he left behind his wife (née Zhong) and two sons. In order to raise the family, Mrs. Wu adopted a son-in-law, Zhang Agou, to serve as the widow’s new husband.

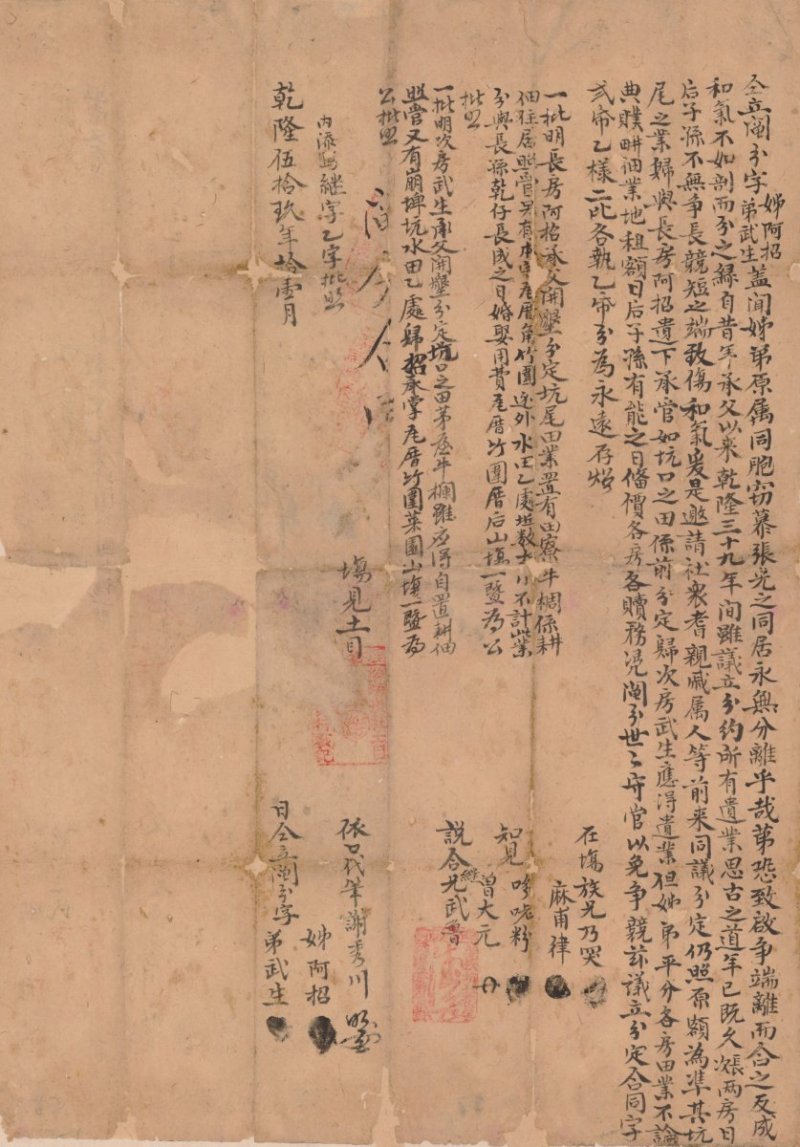

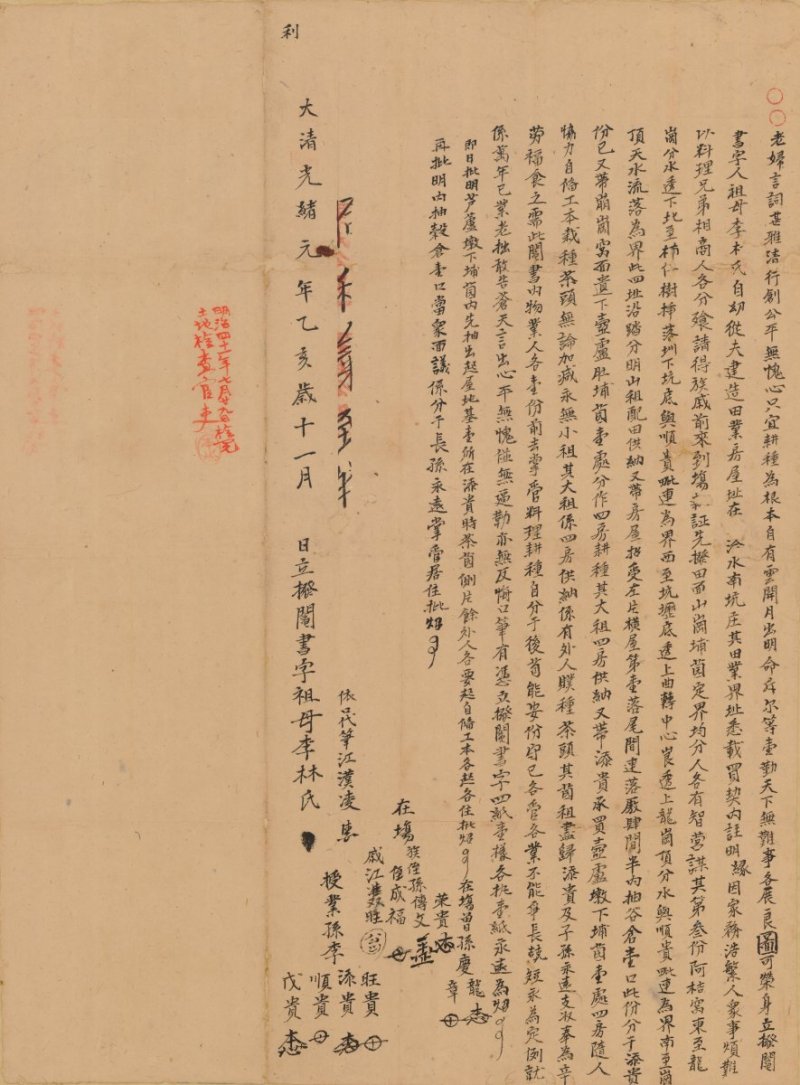

In traditional marriage life, husbands were highly respected by their wives. Only when there were no male elders in the family did the adult females preside over the household. For example, Chen Ling (1875-1939, wife of Lin Jitang of Wufeng) became the head of household after her husband died. Her diary recorded the affairs such as the management of servants, land sales, farmland rentals, and ancestral worship. In some cases, adult women with no patriarch in the family could not only deal with family property matters but also attend the contract signing processes.   The document on the left is an allotment agreement held by A-Zhao and her younger brother, Wu-Sheng, in 1794. The document on the right is such an agreement as made by Mrs. Li (née Lin) in 1875. The plain aborigines (Pinpu tribe) woman A-Zhao could share family property and held the same position with men. In contrast, the traditional Han women like Mrs. Li could not inherit family property. Only when there were no male elders could women preside over the family distribution at the witness of the relatives. |

|