|

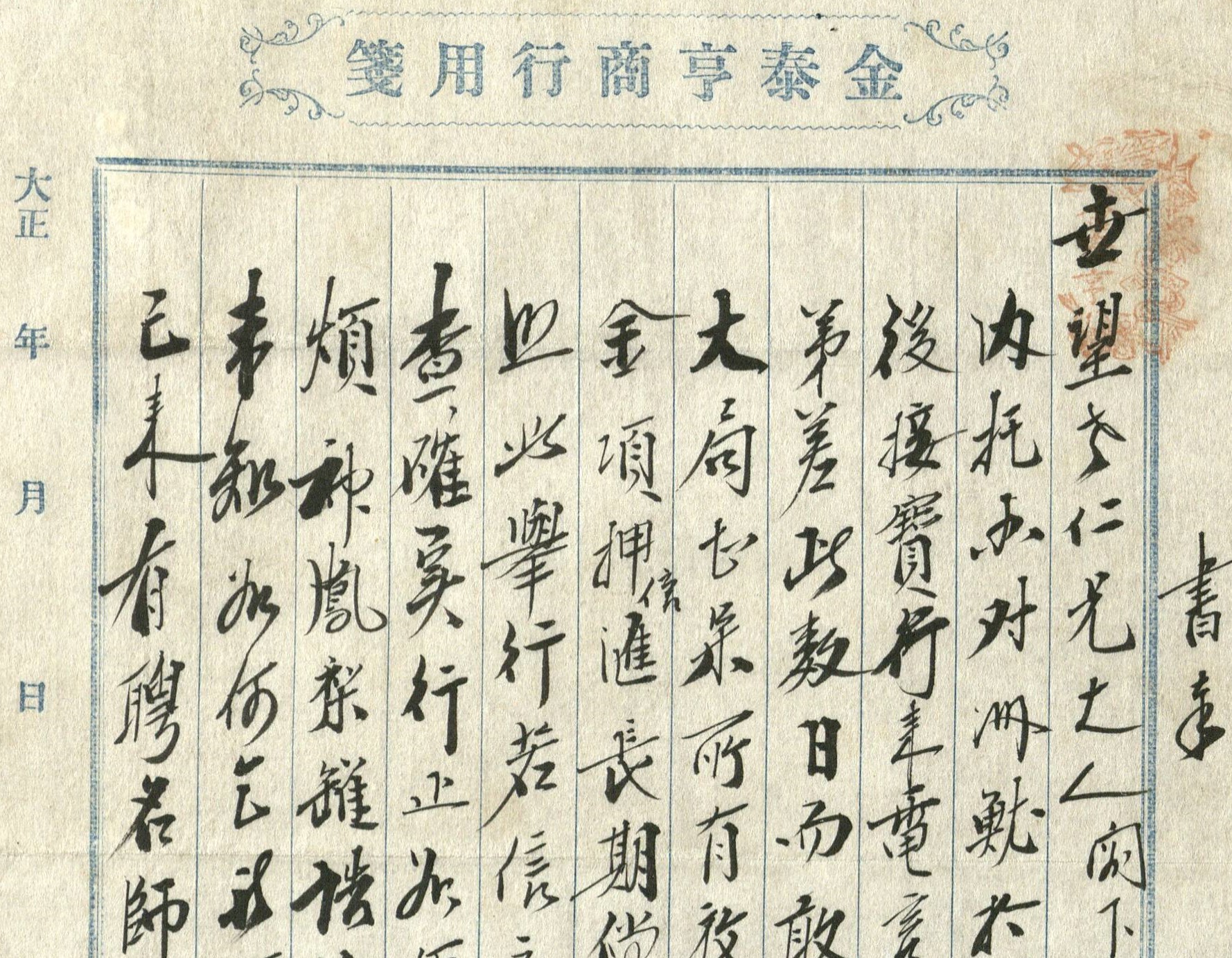

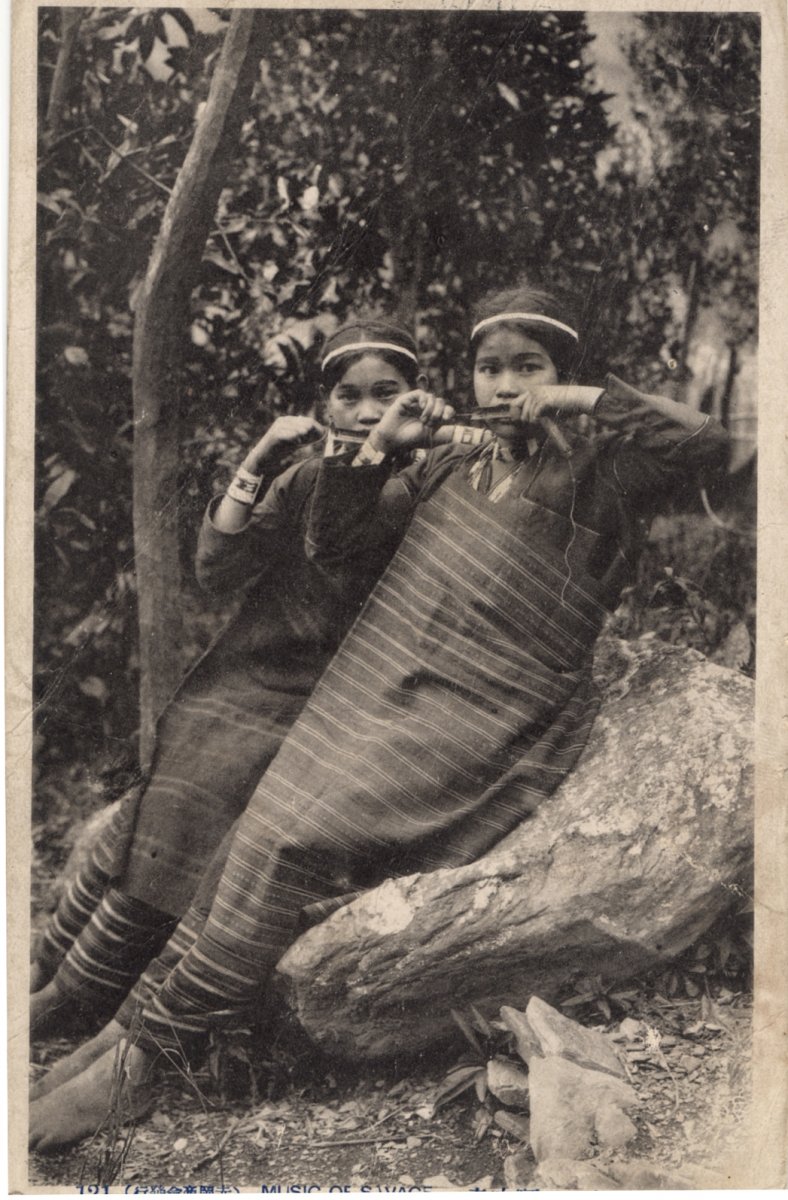

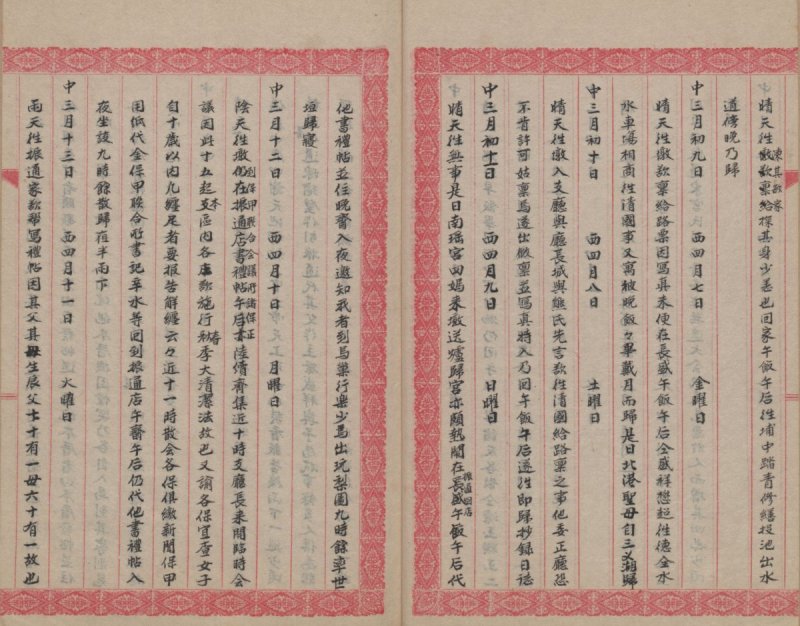

The lives of women in traditional society, whether rich or poor, were centered around the family. Those from the gentry families were especially secluded in their residence due to the immobility caused by footbinding.  Photo1 (Courtesy to the Pingdong Hsiao Family Ancestral Hall) Photo1 (Courtesy to the Pingdong Hsiao Family Ancestral Hall)  Photo2 Photo2 Photo3 Photo3Photos 1 and 2, taken during the Japanese colonial period, portray women of the Hakka ethnicity in Pingdong and a pair of indigenous women from the Wushe area, respectively. Photo 3, from the same era, is entitled “Women from the Min clan with feet bound.” Compared to the natural feet of the Hakka and indigenous women, the feet of women from traditional Han families were bound by mothers at the age of four or five; this practice was especially prevalent in families originating from the southern Fujian province of China. The more exquisitely and finely bound a woman’s feet were, the higher the price she would fetch on the marriage market. During the Japanese colonial period, the practice of footbinding was considered as an uncivilized custom. The government implemented a series of policies, ranging from persuasion of the gentry, to the “anti-footbinding movement” through the Baojia system (a community-based law enforcement system, also known in Japanese as the Hoko system) that resulted in a significant reduction of the number of women with bound feet.  “This Diary of the Shuizhu Villa’s Host (Zhang Lijun),” October 4, 1911. “This Diary of the Shuizhu Villa’s Host (Zhang Lijun),” October 4, 1911.Zhang Lijun, the baozheng (a communal authority under the Baojia system) of Fengyuan, recorded in his diary that in a Baojia meeting held on April 10, 1911, the branch director ordered all baozhengs “to check all girls under ten years of age within their respective baos (a unit comprised of multiple families) for bound feet; and that those who were found to have bound feet must file a report upon having their feet unbound.” This record illustrates how the Government-General of Taiwan promoted the unbinding policy through the Baojia system.

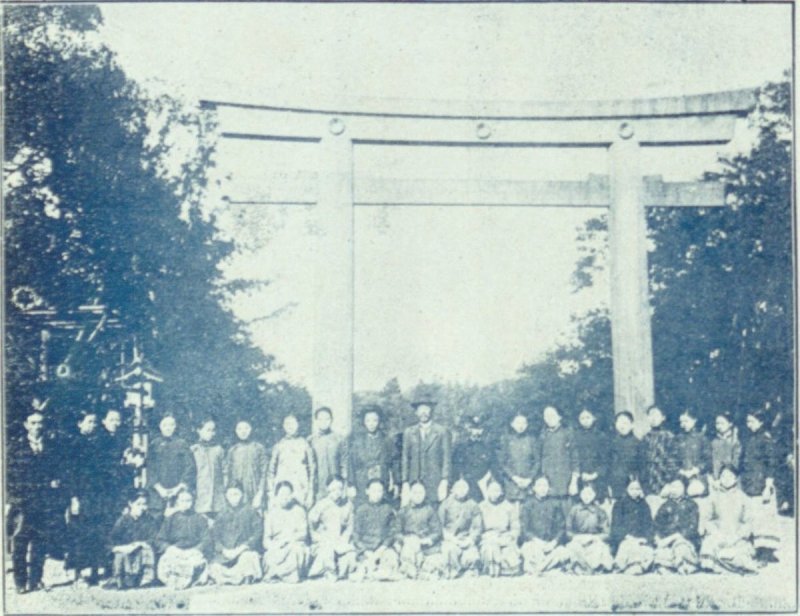

Following their physical emancipation, women walked out of traditional family life and entered new schools to receive education, dismissing the conventional notion that “a virtuous woman is an ignorant woman.”  This photo is of thirty Taiwanese female students of the Taihoku Girls High School worshiping at the Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo, in November 1920. This photo is of thirty Taiwanese female students of the Taihoku Girls High School worshiping at the Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo, in November 1920.In order to fulfill their goal of colonial control, the Japanese colonial government invited Taiwanese students to come to Japan, enjoy its scenery and visit its historical sites; meanwhile, these female students were essentially taught how to act as Japanese women, in that they were educated in Japanese traditional and popular customs, as well as instructed in Japanese civil and military culture.

Women from well-to-do families who were eager for education would even study abroad, mostly in Japan. Except for those who attended missionary schools due to religious reasons, many of them majored in medicine, household management, music, and arts.

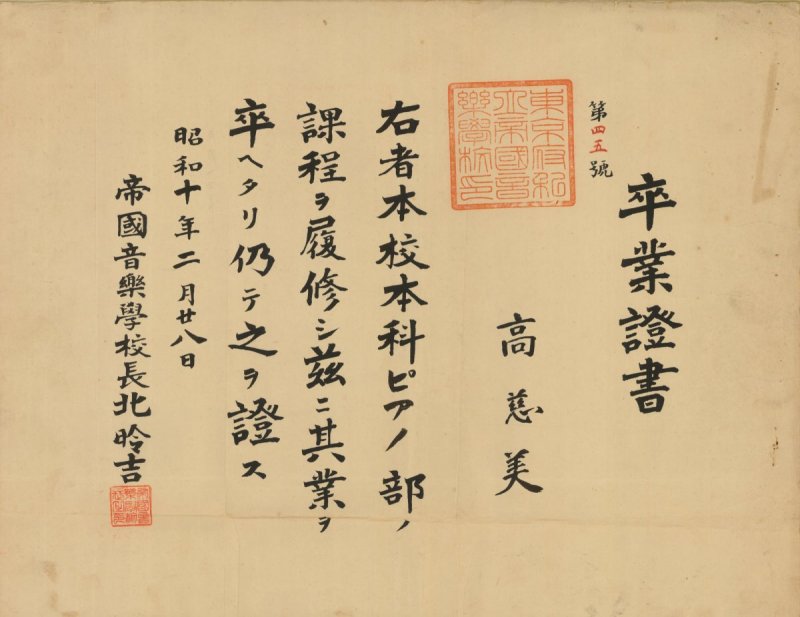

The document on the left is Ms. Gao Cimei’s diploma received from the Tokyo Imperial School of Music in 1935.Gao Cimei (1914-2004, daughter of Dr. Gao Zaizhu) served as a music professor at the Taiwan Normal University in the postwar period. When she was a fifth grader at the Baiko Women’s College in Japan, she wrote down her feelings and experience in her diary. |

|