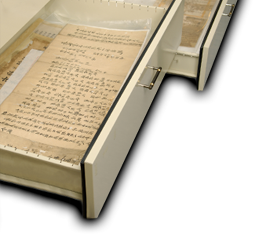

Author & Photo: The Archives of Institute of Taiwan History The development of Guanxi area began in 1791, when Wei Agui of Zhuqian Village arrived the east side of Xinpu, including Laogengliao, Dahankeng, Shigangzi, Xiananpian, Maozipu, and Pinglin. In 1793, Chen Zhiren from Quanzhou Prefecture led the 「Lianjisheng」 Estate to settle around Shangnanpian Village and named it 「Meili Village」 for its gorgeous scenery. The very next year, Lianjisheng Estate was forced to leave by the indigenous Atayal Tribe, and Wei Agui took over the development project and renamed Meli Village to 「Xinxing Village.」 After Wei Agui passed away, his grandson inherited the business and established a new 「Xinhehe」 Estate to expand the farmland with Dai Nanren, Huang Lubo, and Chen Fucheng in 1849. Their development completed in 1850. At the same time, as the mountains surrounded the terrain with only one opening in the west, the shape of this area was like an earthen urn for 「Xiancai (pickled vegetables).」 Therefore, 「Xinxing Village」 was renamed as 「Xiancai Wong」 or other names with similar sounds, such as Xiancai Peng or Xiancai Feng. In the Japanese colonial period, perhaps because 「Xiancai」 was in assonance with Japanese word 「Kansai (Guanxi in Chinese characters),」 Xiancai Wong and Shigangzi were renamed to 「Kansai (Guanxi) Village.」 Later, the administrative regions were changed several times, but the word 「Guanxi」 continued to be used till the present day. The Institute of Taiwan History has once exhibited a collection of 68 documents of Guanxi region, and most of them were purchased from private collectors in the Fengyuan region. The earliest document is in the year of 1825, and the latest one is in 1923. This collection comprises land records, personal contracts, licenses, and property allotment agreements among heirs and devisees of the Zhang family of Hudu Village, as well as relevant documents about the offspring of Wei Agui. This collection is a source for understanding the development of Guanxi area, especially the developing trace of the Zhang family, the uniqueness of Hakka written language, and the early interactions between the plain aborigines and the Han settlers. In addition, these documents, which contain 7 marriage contracts and personal agreements, are precious for studying history of women's life from the late Qing to the early Japanese colonial period. Those marriage contracts all belong to 「exceptional case marriage (Bianlihun).」 The so-called 「exceptional case marriage」 means a marital relation without a formal wedding ceremony; for example, the custom of marrying into and living with the bride's family to support the ex-husband's household or to continue lineage as well as the practice of adopting child brides to save the spending of betrothal money. Such marriages reflect the profound patriarchal nature of Taiwanese society. In marriage, women's value merely lies in the labor force and the capacity of giving birth. Once the husband dies, a family often needs a new son-in-law to support the household under economic pressure. These documents often state clearly about the right or obligation relations of the arrangement of future children, the inheritance of property, and the duty of ancestral worship, etc. Besides, in a poor family, if a husband dies without a son, the widow may be married to someone else or brought back by her parents that would have to pay an amount of money to the husband's family. Women's voices are missing in these marriage contracts or agreements regarding personal affairs, and such condition manifests women's compromises and sorrow in marriage and family economy. |

|