|

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 signaled the advent of the Japanese invasion of China and in the early phases of the war the Japanese forces swiftly captured major cities including Peking, Tianjin, Shanghai and Nanjing. Following in the footsteps of the army, the civilians in the Empire of Japan also made their way into occupied territories in China. Besides being conscripted for the battlefields, the Taiwanese came to serve in various puppet regimes and secret agencies. A China under Japanese occupation offered new prospects for the Taiwanese. Travel writing on China was serialized in 17 accounts with as many as 110 articles in “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” after 1938, with destinations ranging from Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Guangdong, Shantou, the Island of Hainan, to Xiamen and others. Of these, those accounts most in keeping with continuity were written by Feng-Yuan Chen, the chief financial officer for “Taiwan Shin Min Pao”, and war correspondent Kiyoshi Takeuchi. Shenqie Zhang, a prominent figure in activist and literary circles, in the account of his travel to Beijing in 1938 gave his opinion on the place of the Taiwanese people in Japanese-Chinese relations.

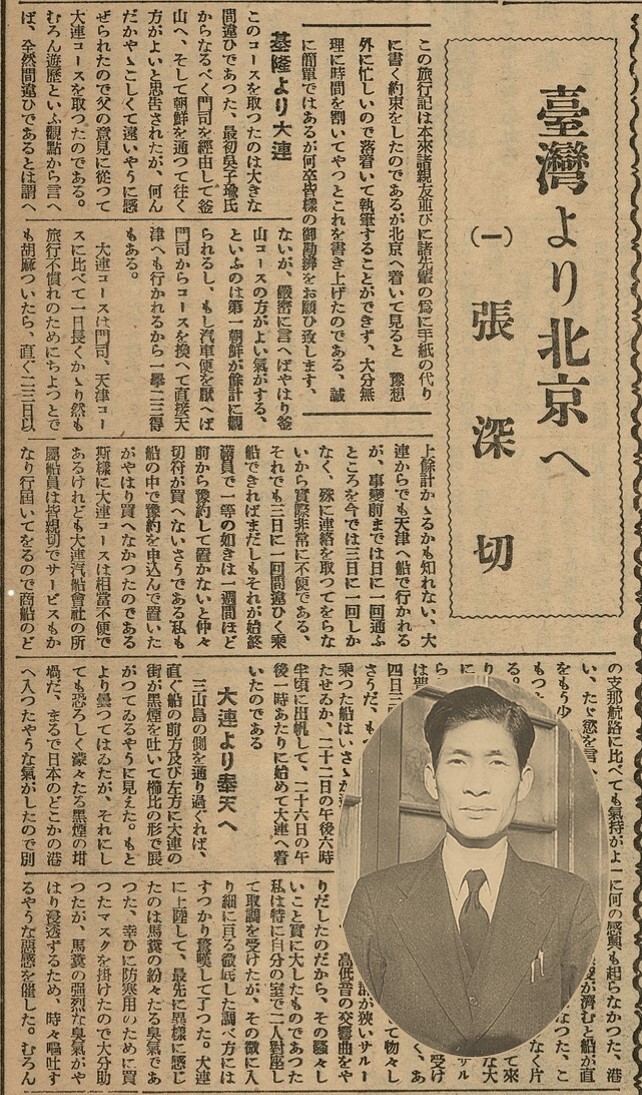

Shenqie Zhang (1904 – 1965), from Caotun, Nantou, pursued his studies in Japan and China in his youth and was keen in political and cultural movements. In 1938, he was invited to take up position as training director and professor in the National Art School of Beijing and taught the Japanese language in the Shin Min College. In 1939, he was asked to organize “Chinese Literature” and served as its chief editor as well as publisher. He was compelled to resign from his positions and returned to Taiwan in 1940 as a consequence of an internal conflict in the art school and the college. In 1941, he was introduced to new job as the editor of the Shin Min Printing Press in Beijing. He also composed the work “Essentials of the Japanese Language”. He took time to write article “From Taiwan to Beijing”, addressing the course of his travel in February 1938 and to be serialized in four chapters and published in “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” in April 1938 (Figure 1). In 1941 he followed up on that with another article, “Thoughts on Beijing”, to appear in 11 chapters in “Shing Nan News”, sharing his experiences and findings of his three years in Beijing.

Figure 1: Shenqie Zhang’s Account of Travel Published by “Taiwan Shin Min Pao” on 21 April, 1938

Source: “Taiwan Shin Min Pao, No. 2589 (1938-04-21)” (T1119_02_076_0020), “Historical Materials – Taiwan Shin Min Pao Publishing House” (T1119).

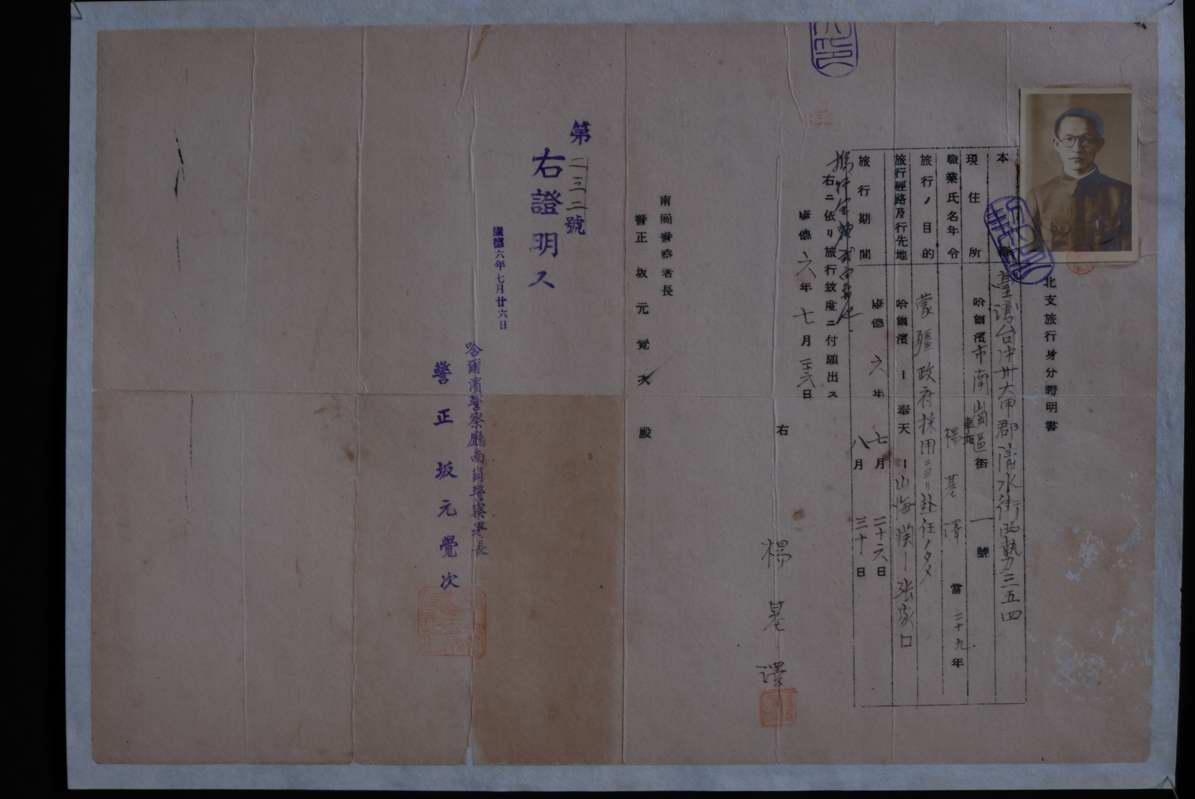

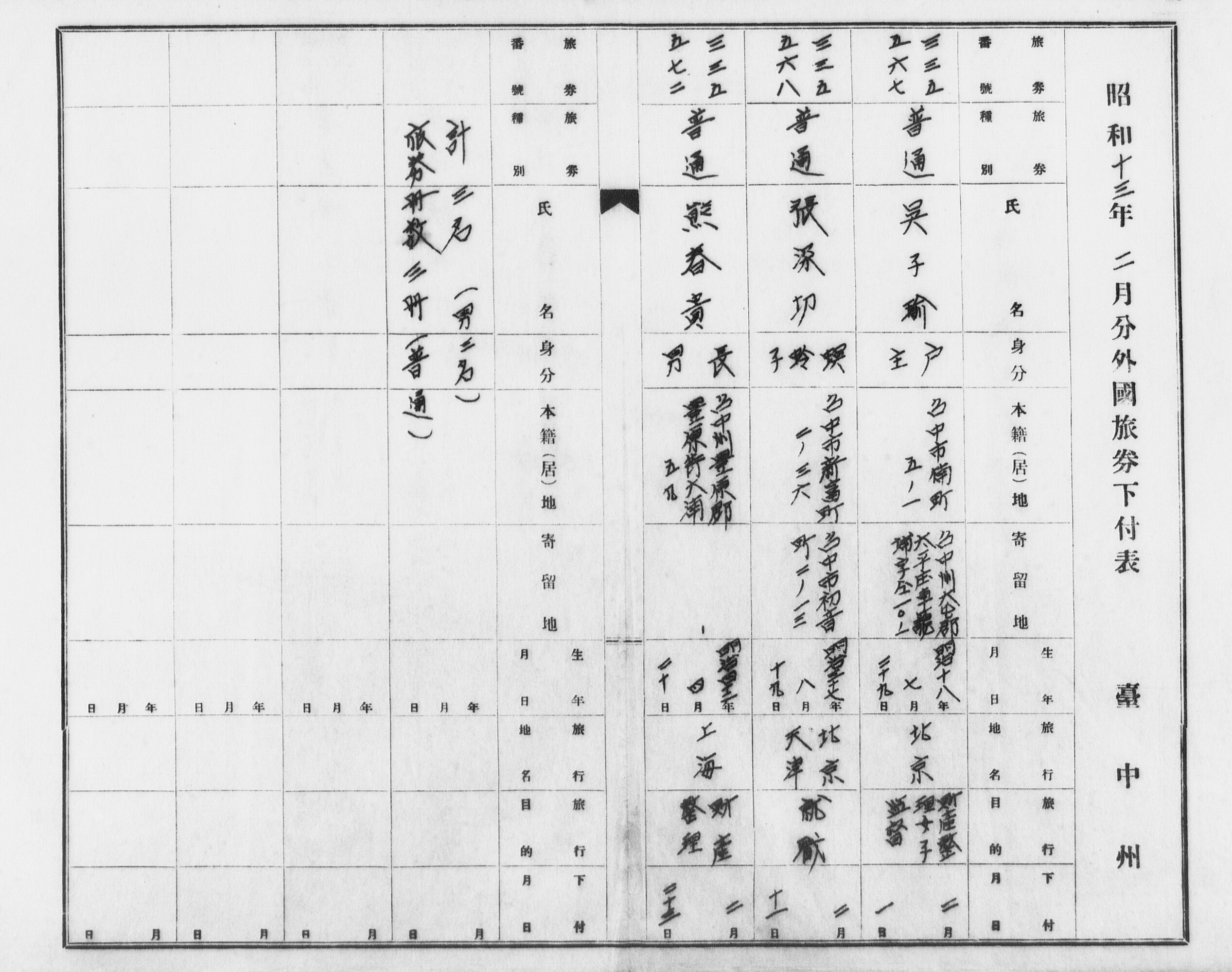

Figure 2: Copy of Shenqie Zhang’s Booking Travel Ticket to Beijing

Copy of Shenqie Zhang’s travel ticket to Beijing, the purpose of travel being employment and the identity being ming ling zi (namely adopted son). His adopted father was Yushu Zhang, a Lishe member. Source: “Foreign Passport List, January – March 1938, Government-General of Taiwan” (T1011_03_156), “Passport Submission and Return of List, Government-General of Taiwan” (T1011)

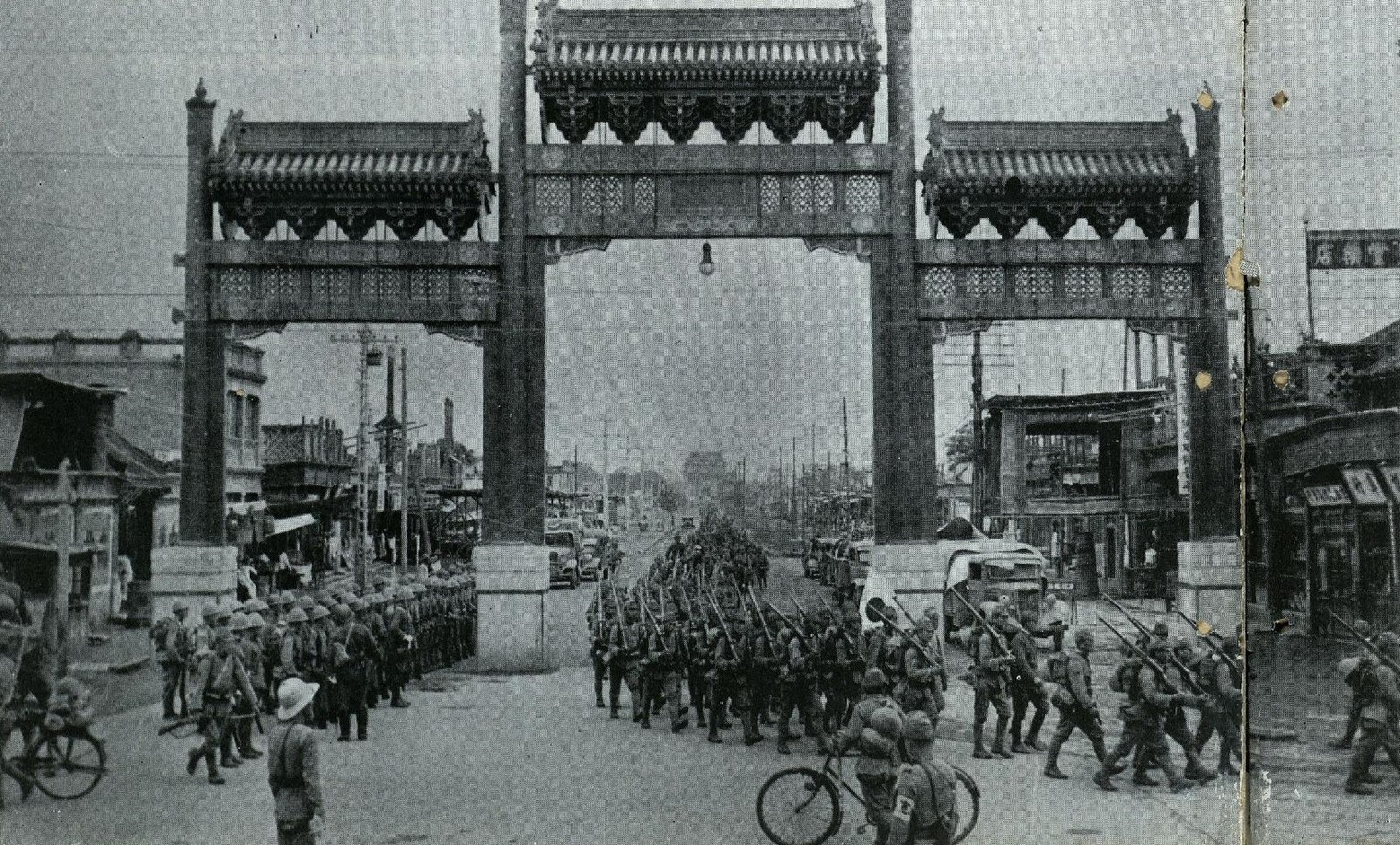

Shenqie Zhang traveled to Beijing in the wake of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937. In late July of that year, the Japanese forces occupied Peking (later renamed Beijing) and Tianjin. A puppet regime – the Provisional Government of the Republic of China – was established in Beijing by the Japanese and staffed with pro-Japanese elements. The occupied zone was garrisoned to maintain public order and general control. As Japanese citizens, the Taiwanese enjoyed nearly identical treatment as the Japanese within the occupied zone, given protection in terms of belongings and personal safety. The bilingual Taiwanese, who could potentially help to bridge the gap in views between the Japanese and Chinese people, did not have much trouble finding official positions to take up. Some Taiwanese people relocated to China for work accordingly, with Taiwanese expatriates there often serving as contacts. By the end of the war, more than 500 had been living in Beijing among whom was Shenqie Zhang.

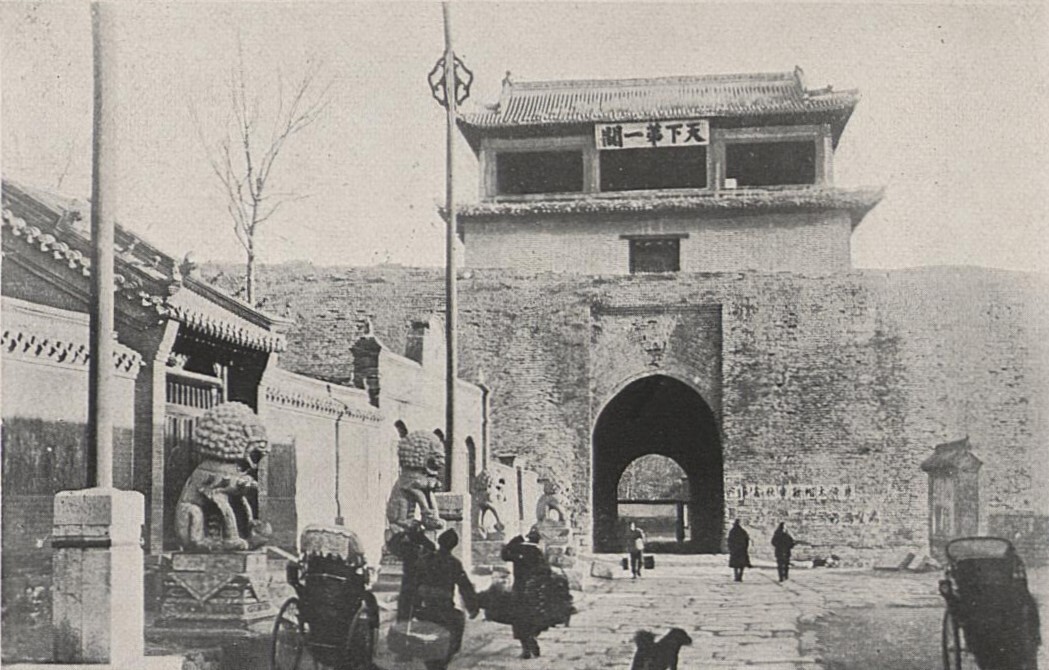

Figure 3: Scene of the Japanese Forces Entering Beijing through Chaoyangmen on 8 August 1937

Figure 4: Scene of the Establishment of the Japanese-backing Provisional Government of the Republic of China on 15 December 1937

Source: Japanese Economic View, edited by Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, Osaka: Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, 1938, no page, Classical Literature Database of Taiwan Studies, Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica (B2401_00_00)

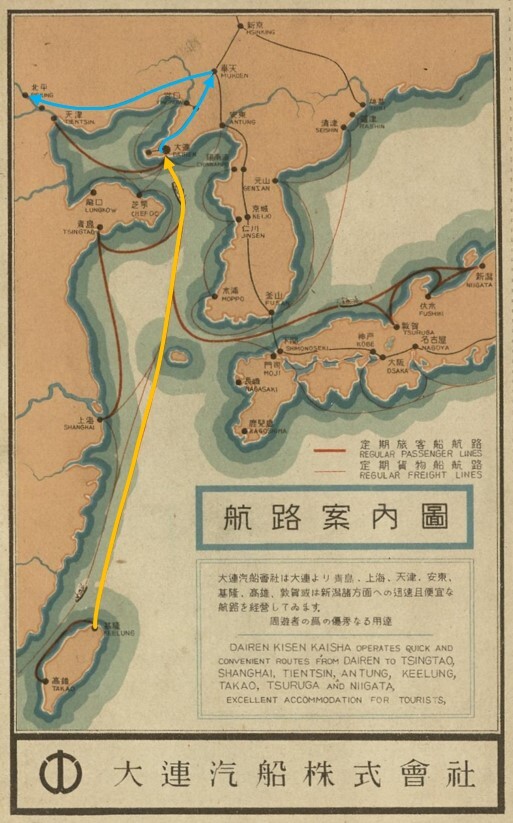

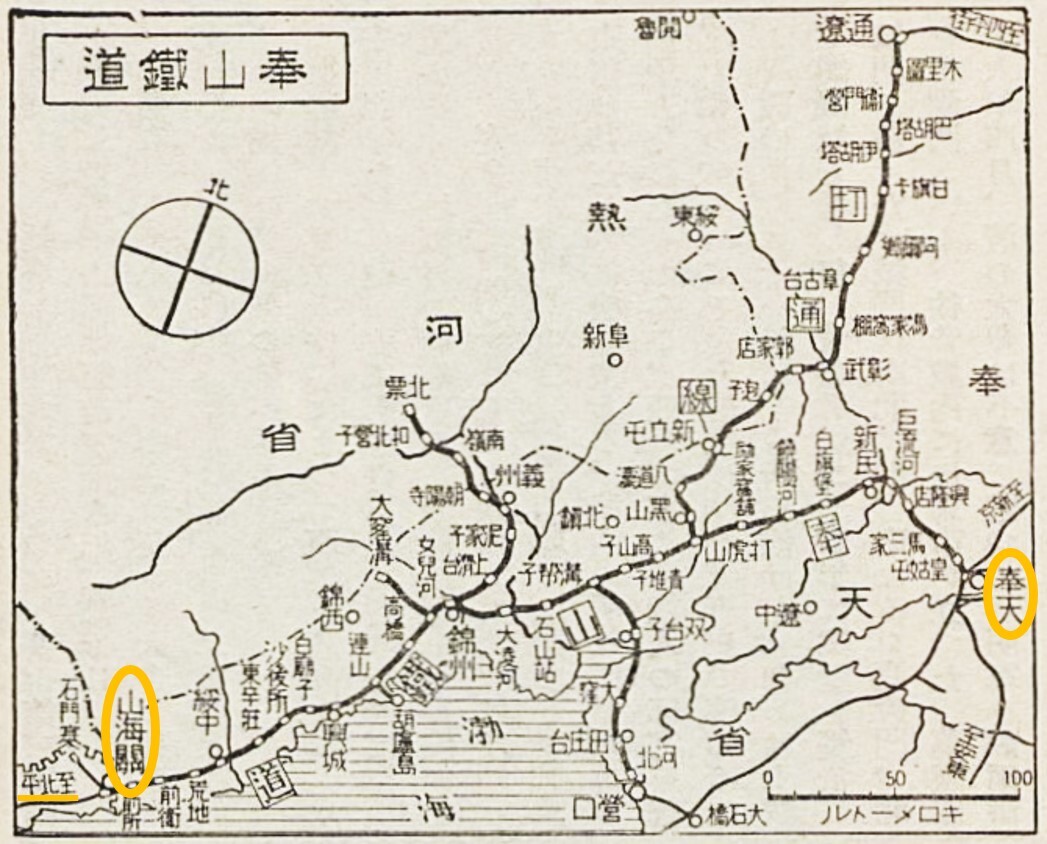

Beijing was situated inland in northern China which required switching from the sea route to travel overland in any journey from Taiwan. As multiple sea routes were available, Shenqie Zhang pondered over the possible routes to be taken before his departure. He considered the advice of an elder acquaintance Zi-Yu Wu, who had been in business in Beijing. It would take him from Moji, Japan, to Busan, Korea, by ferry and on to China by land through Korea. But he concluded that the distance involved would be too great. An alternative would be a cruise from Moji to Tianjin whose proximity to Beijing eliminated the trouble with boarding a train. But cruise schedule turned irregular at the onset of the Sino-Japanese war and tickets were hard to get hold of. In the end, Shenqie Zhang listened to the suggestion of his father and opted for a cruise operated by Dairen Kisen K. K. from Keelung to Dalian (yellow line in Figure 5). This trip was more time-consuming but the service on the cruise proved decent enough. On his arrival in Dalian, Shenqie Zhang turned to the railway (blue line in Figure 5) and took the South Manchuria Railway for his journey to Mukden (Shenyang today) and made a brief stop there. He then switched to the Mukden Railway for Beijing, reaching the Shanhai Pass Station deep into the night and finally ending his journey in Beijing in the morning.

Figure 5: Shenqie Zhang’s Route of Travel for Beijing

Figure 6: Mukden Railway during the 1930s

Upon landing in Dalian, the passengers were taken for health checks before being kept in the noisy waiting area in the hall for the police roll call and identity checks. For his part, Shenqie Zhang was interrogated one on one in a room in a manner he found marvelously meticulous. Once ashore, Shenqie Zhang was alarmed at the pungent stench from horse fecal matters, a situation unrelieved by his cold-proof mask (マスク). Carriages and rickshaws constituted the transportation in Dalian in the main. After his meeting with Yuan-Xuan Fu, a doctor in medicine serving with the Da-Tung Hospital, Shenqie Zhang hired a carriage for a tour of the Dalian streets. He thought it a good bargain to have paid 1 yen and 30 sen for a trip lasting between two and half hours and five hours. After a round in the most prosperous quarters in the city, he felt like in Shanghai.

Figure7: Cargo Liner Affiliated with Dairen Kisen K. K. Company, Ltd

Figure 8: Passenger Waiting Area at the Dalian Seaport

Figure 9: Carriage and Rickshaw in northeastern China in the 1940s

Figure 10: Street View of Dalian in the 1930s

Part Five: Old Acquaintance in Mukden After a Russia meal, which he found unpalatable, Shenqie Zhang took an overnight train to Beijing. The line between Dalian and Mukden was typically busy; trains were often full and even first-class seats were difficult to come by. Shenqie Zhang decided to get off the crowded train at Mukden, where he was to spend the night, and contact Hsing-Hsien Chang, who worked for the Manchuria Railway (the South Manchuria Railway Company, Ltd.) and was the first Taiwanese athlete to compete in the Olympic Games. Hsing-Hsien Chang received him in Mukden upon his arrival. As the regular hotel that Shenqie Zhang had in mind was full, he had to go for the pricier Whoville Hotel (ホービルホテル) which also happened to be full but a special request vacated one room for him. Shenqie Zhang paid a visit to the house of Hsing-Hsien Chang on the next day and met another pair of guests, Ji-Zhen Yang and his wife, from Hsinking (or Changchun). Yang also worked for the Manchuria Railway and they joined for lunch. As the wives of Hsing-Hsien Chang and Ji-Zhen Yang prepared the meal, Shenqie Zhang had the pleasure of familiar cuisines in a foreign land, and shared the happiness of the newly married couples. Accompanied by Ji-Zhen Yang, Shenqie Zhang returned to the Mukden Train Station and boarded the Mukden Railway Line (Mukden-Shanhai Pass) for Beijing. Neither Ji-Zhen Yang nor the clerk at the station was able to book a seat for him for the train was totally full. It was also a journey that would last in excess of 20 hours. Shenqie Zhang then recalled the advice that he received sometime earlier: take a seat available at the moment and wait for his turn for the sleeper, which helped with the toil of a long journey. Shenqie Zhang found the Mukden Railway less well-equipped than the Manchuria Railway but the food on offer agreeable. As it was already midnight by the time the train reached the Shanhai Pass, a clear view of the “First Pass under Heaven” was regrettably impossible in pitch-darkness on his part. As the Shanhai Pass lay on the borders that Manchukuo and the Republic of China shared, the trains passing through it began to check papers of travel (Figure 11), travel tickets (passports) and the luggage. Shenqie Zhang noted that the examination conducted on non-Chinese passengers was much less rigorous. A pleasant talk with the soldiers on the train in the next morning was followed by their arrival in Beijing at 11 am.

Figure 11: Yang’s Paper for Travel through Northern China

Figure 12:“First Pass under Heaven” – The Shanhai Pass Part Six: Attraction of Imperial Capital Privileged as the capital of the Chinese Empire for hundreds of years and with an excellent concentration of Chinese cultural achievements, Beijing greatly charmed Shenqie Zhang with the magnificence, elegance and beauty of the towers in its palace. Shenqie Zhang rendered an overview of Beijing in his account of travel, with many praises for clement weather, green landscape, fresh air, straightforward townsfolk, good public order and so on. Special praise was reserved for the transportation, which was convenient with affordable rickshaws conducted by honest pullers and coachmen with little concern for safety. Based on his observations, Beijing’s consumer economy was centered on the hotel industry and catering, including hotels, cafes, ballrooms and restaurants. The Japanese were best represented among their owners to be followed by the Koreans (peninsular residents) while the Taiwanese were usually found in government agencies. He thought that it was the Taiwanese who were most likely to rise to the occasion regarding the crucial task of promoting “Japanese-Chinese Friendship”.

Figure 13: Postcard Showing the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, Beijing

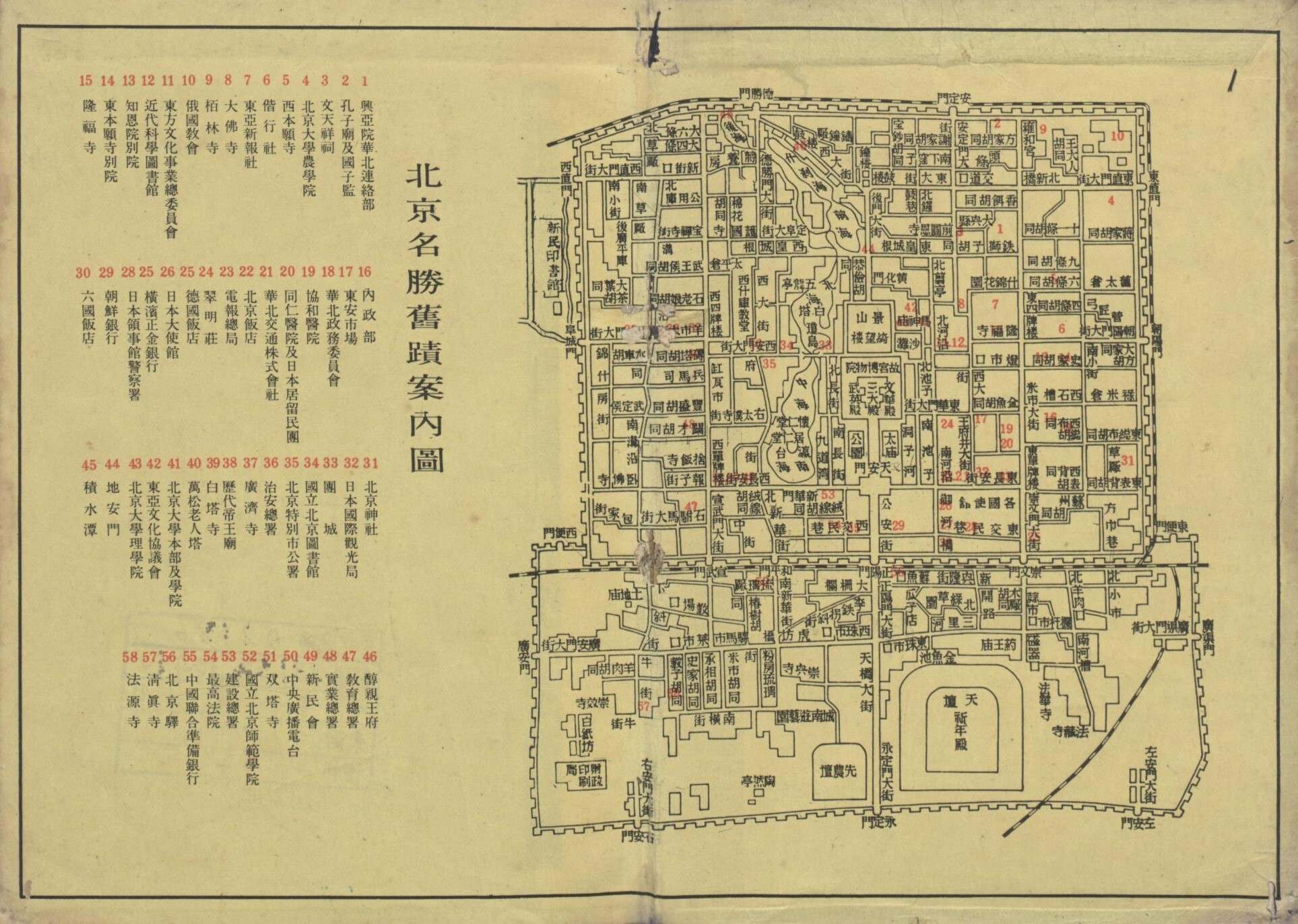

Figure 14: Attached Map Labeled with Notable Monuments in Beijing, “Peking Annaiki”, 1942

Figure 15: Rickshaws in Beijing

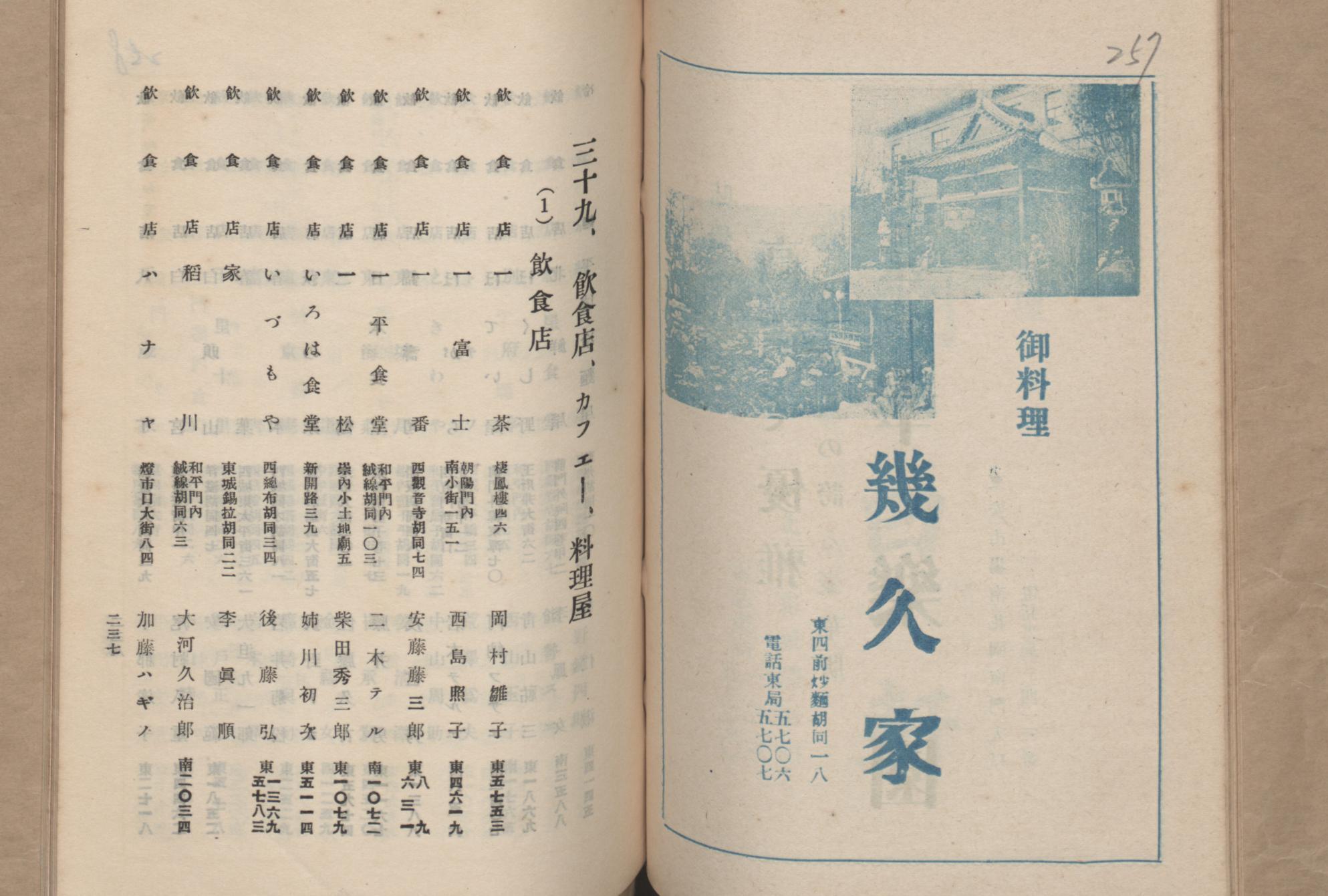

Figure 16: List of Names of Dining Shop (restaurant) in “List of Beijing Business Titles” |

|