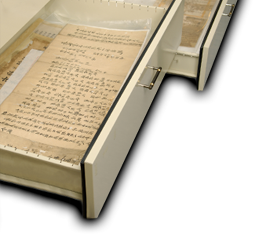

Author: The Archives of Institute of Taiwan History

Du Xiang-guo was a member of local gentry and industrialist in Dajia Town, Taichung County. His father, Du Qing, was dedicated to improving quality of Dajia Straw hats and mats and exporting them to Europe and the United States. Being a successor of his father’s business, Du Xiang-guo was active in manufacturing and financial industry. The Du Xiang-guo Papers, with coverage date from 1908 to 1946, contains his correspondence on business matters, diaries during attending schools, and literary works.