The beginning of the 19th century saw the first wave of Han Chinese migrating from Ilan to the Hualien area for land reclamation. These early immigrants settled near the estuary of the Hualien River. However, seawater intrusion caused floods, affecting the salinity and quality of the soil; thus forcing them to move further north to the banks of the Meilun River. In this area at high tide, the Kuroshio flowing from south to north collided with the water of the Meilun River. The Hans therefore named the coastal area “Huilan”, literally meaning whirling waves. In Hokkien, Huilan sounded like Hualien. During the Qing Dynasty, this area began to be called “Hualien Port” and continued to be thus named when Japan took over Taiwan. During early Japanese colonial rule, Hualien was under the jurisdiction of Taitung County. In 1908, it was renamed “Karenko (花蓮港, Hualien Port) Town”. In September 1920, following the enactment of a new statute, the old political division system was abolished. Similar to that used in mainland Japan, the structural hierarchy now comprised seven administrative divisions, one of which was the “Karenko (Hualien Port) Prefecture” and later renamed “Karenko (Hualien Port) City” in 1940.

1. Katagumi: Japanese Pioneer in Hualien development

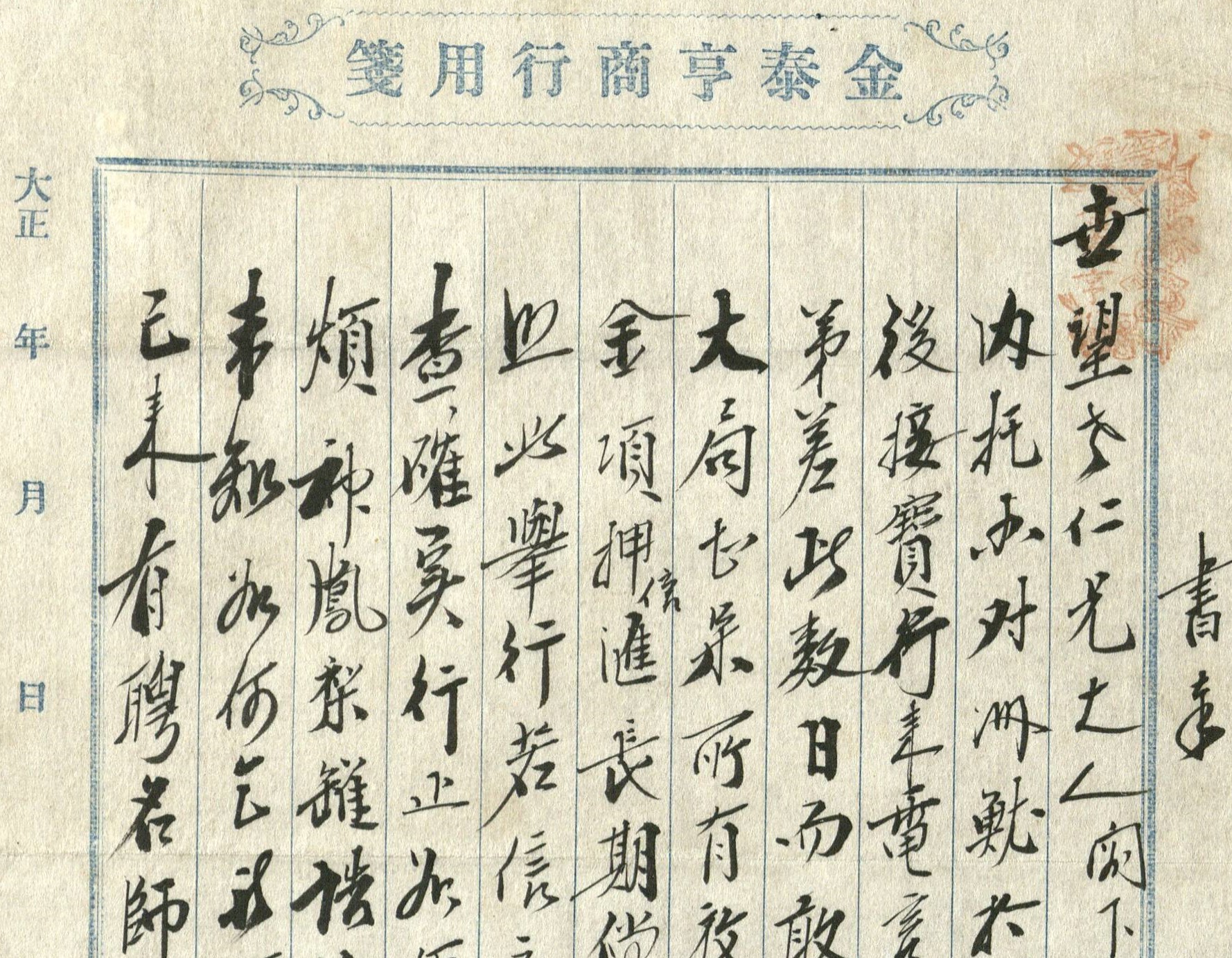

Under early Japanese rule, the administration of the Government-General of Taiwan had dual focus; administering the development in the west and subduing the aborigines in the east. Private enterprises including the Katagumi (賀田組) and Ensuiko Sugar Refining Co., Ltd (鹽水港製糖株式會社). were the key players in the development of eastern Taiwan. In 1899, a Japanese entrepreneur Kata Kinzaburo (賀田金三郎, 1857-1922) established the Katagumi Reclamation Company with authority granted by the Government-General of Taiwan to reclaim land between Hualien and Taitung. The area reclaimed, totaling approximately 19,822 hectares, included Karewan (the present-day Jiali Village and Jialin Village in Xincheng Township), Wuquancheng (the present-day Zhixue Village in Shoufeng Township), the wilderness surrounding the Wanli Bridge of today’s Fenglin Township, and Jialulan (the present-day Jici Village of Fengbin Township).

The Katagumi planted sugar cane, mint, tobacco and other crops in the reclaimed land and was also engaged in camphor production, animal husbandry and immigration business. However, land reclamation posed threat to the living space of the aborigines, causing incessant clashes. The Wili Incident, a serious conflict that broke out in 1906 due to a wage dispute with Truku camphor miners, resulted in 25 Japanese decapitated, including the chief and officials of Hualien Subprefecture as well as staff of the Katagumi. Not only did the reclamation ventures of the Katagumi suffered a setback, its immigration undertakings also fell into a stalemate. In 1909, Kata Kinzaburo had to hand over the franchise of land reclamation to Ensuiko Sugar Refining Co., Ltd.

Figure 1 Houses of Kadagumi Immigrant Village in Wuquancheng

As can be seen, the immigrant village had poor living resources for self-sufficiency. Other factors including immigrants unaccustomed to the climate/food/environment led to failure in the initial wave of Japanese immigration.

Source: Document Section of the Government-General of Taiwan, ed. Taiwan Photobook (Taipei: Editor, 1908), Taiwan Rare Book Collections.

2. Public Immigration Venture: Establishing Immigrant Village model development

Following the failure of private immigration undertakings by the Kadagumi, the Government-General of Taiwan turned it into a public venture in 1910, recruiting immigrant farmers from Japan and establishing the government-run “Yoshino Immigrant Village” in Hualien. Reasons behind promoting immigration included relief of pressure on growing population and limited rural resources in mainland Japan. Hence, rewards were offered for immigrants from the farming sector. Moreover, increasing Japanese settlers in Taiwan would facilitate colonial rule and foster assimilation of the Taiwanese. In addition, experience accumulated in Taiwan would better prepare Japan for future advances into the tropical area.

The Yoshino Immigrant Village earned its name because most of the immigrants came from Yoshinogawa in Tokushima Prefecture, Japan. Despite having been screened and selected, the immigrants had difficulty acclimating to the hot humid environment in Taiwan. Moreover, they were under the threats of being infected with tropical diseases such as malaria and scrub typhus, invaded by the aborigines, and attacked by natural disasters including typhoons and earthquakes. Worse still, the poor irrigation facilities made it hard for them to achieve self-sufficiency. All these results in a declining number of immigrants and obstacles for land reclamation. The situation gradually changed under the efforts from the Government-General of Taiwan in improving the agricultural environment and providing medical care. With the immigrants mastering the skill of cultivating tropical crops and getting accustomed to the local climate, by 1919 the immigrant village could finally enjoy economic betterment.

Rice and sugarcane were the main crops in the initial establishment of the Yoshino Immigrant Village. In 1913, tobacco leaf was experimentally cultivated; and since 1930, tobacco leaf production had spread to all government-run immigrant villages across Taiwan. Upon harvest, the tobacco leaves were processed into the widely popular Red Jasmine Cigarettes. Although the area dedicated to tobacco leaf cultivation was small, tobacco was the third main crop of the Yoshino Immigrant Village after rice and sugarcane due to the considerable economic benefits generated.

Figure 2 Yoshino Immigrant Village in Hualien Port

Source: Endo Kanya, ed. Views of Campaign Against the Aborigines in Formosa (Taipei: Endo Photo Studio, 1912), Taiwan Rare Book Collections.

3. Truku War, 1914

The 1906 Wili Incident with Japanese decapitated by the Truku was a severe blow to the reclamation ventures of the Kadagumi. In the same year, Sakuma Samata (佐久間左馬太, 1844-1915), a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, was appointed the fifth Governor-General of Taiwan. Extending Japanese control into the aboriginal regions was his main mission. Determined to subdue the Truku by force, he sent warships to shell the tribal settlements and tried to contain the tribesmen with frontier guards. However, this aroused further resistance from the Truku.

In 1910, the “Five-year Plan of Aboriginal Governance” (五年理蕃政策) was put forward by the Government-General of Taiwan, with details of a military crusade against the Truku, the yet-to-be-subdued aboriginals in the north. To prepare for attacking the Truku, the Bureau of Aboriginal Affairs began surveying and mapping the terrain features of the mountains around Taroko from 1913 so as to have a full grasp of the geographical environment and to plan the route for military operations. At the same time, roads were laid, telecommunication equipment was installed, temporary hospitals were built and rescue squads were formed, all in preparation for combat.

In 1914, led by the Governor-General Sakuma Samata, more than 6,000 troops and police encroached upon Taroko from the east and the west. Not only were the Truku outnumbered, they were also poorly equipped, leaving them with no choice but to surrender. In July of that year, the chieftain Holok-Naowi led the tribesmen to yield their firearms and ammunition. In August, the Japanese army held a surrender ceremony to declare victory over the Truku. With the war ended, there were no serious resistance or rebellions in the Qilai area of northern Hualien, and various industries could thus develop successfully.

Figure 3 During the Truku War of 1914, the Second Squadron of the Japanese army set artillery and mortar at Mantou Mountain for shelling the aborigines so as to cover and support the infantry in combat.

Source: Photographic Society of Taiwan, ed. Taiwan Photo Book, Volume 2 (Taipei: Editor, December 1914), Taiwan Rare Book Collections.

Figure 4 Japanese troops landing at Hualien Port during the Truku War of 1914

Source: Taiwan Nichi Nichi Shinpo, ed. Photo of Crusade Against the Truku (Taipei: Editor, 1915), Taiwan Rare Book Collections.