|

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that killed millions in Europe and Asia during the Middle Ages, causing a sharp decline in population. At that time, the cause of the disease was unknown, but quarantine and isolation were adopted as treatment and prevention measures. With the development of bacteriology at the end of the 19th century, the bacterium Yersinia pestis was identified. Symptoms of bubonic plague infection included headache, chills, fever, fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes. In 1894, the plague ravaged Guangzhou, Hong Kong and other places in China. In view of the frequent cross-strait exchanges and to prevent the plague from spreading to Taiwan, in April 1896, the Government-General of Taiwan formulated quarantine procedures for ships coming from five ports in China, including Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo, and Shanghai. In May 1896, the first infected case appeared in Anping, Tainan; and the epidemic then spread to Taipei and Taichung. These cities in northern, central and southern Taiwan became epidemic hotspots for the plague that ravaged the entire Taiwan for more than 20 years. Following the outbreak, the Government-General of Taiwan established the “Provisional Committee for Plague Prevention” to deliberate matters related to epidemic prevention and monitoring, and to instruct the local government to carry out preventive measures in compliance with the regulations. Local police set up the provisional quarantine division and subdivisions with serving members comprising both police officers and public doctors. Household registration and inspection were carried out. Those who were infected were immediately sent to hospital. Both quarantine facilities and staff were increased. In addition, household members of the infected were forbidden to leave the house or receive visitors for 7 days. In all public places, quarantine was implemented; households of the infected were disinfected; and home and city surroundings were all thoroughly cleaned. Despite these measures, the plague remained prevalent. That was the golden age of bacteriology, and experts from various countries competed to find the ‘culprit’ of the plague. In December 1896, Ogata Masanori, an authority on bacteriology and a professor of hygiene at the Tokyo Imperial University was invited by the Government-General of Taiwan to investigate the plague. He detected Yersinia pestis in the infected patients, verifying the findings of the French Institut Pasteur experts in Hong Kong that bacteria were transmitted to humans through fleas on rats. This perspective was also confirmed by his inspection of dead rats and related animal experiments. Therefore, he recommended preventive measures including thorough cleaning of the environment, burning of mice caught, and disinfection of plague patients’ bedding. In May 1898, related experts successively came to Taiwan to investigate the plague area. Besides proposing the use of serum treatment, these experts suggested all households maintain good ventilation and be open to sunshine, and demolition of plagued houses. The Government-General of Taiwan established basic epidemiological data from survey results, with detailed descriptions of the origin, spread and etiology of the plague in order to keep up with the system, trend and seasonal changes of the epidemic. In 1900, the Government-General of Taiwan promulgated the "Taiwan House Construction Rules" and the "Taiwan Waste Disposal Rules" for the purpose of managing the urban environment and improving urban environmental hygiene. In the same year, Tsukyama Koichi, a public doctor of the Tainan Provincial Hospital was in charge of the vaccination program. From August 23, 1900 to July 4, 1901, more than 25,000 people in government offices, agencies and organizations, and from households neighboring the infected in Tainan city, Chiayi Street, Puzaijiao Street and other epidemic areas were vaccinated. In 1902, the Government-General of Taiwan launched epidemic prevention focusing on extermination of mice. Using both monetary incentives and compulsory fines, local governments mobilized the public in mice eradication. Other preventive measures included strengthened quarantine at ports, proper isolation of the infected, serum vaccination and promotion of personal hygiene education. In 1907, the Government-General of Taiwan announced the establishment of special sanitation inspection teams to be dispatched to epidemic areas for plague prevention and control. Their duties also included giving lectures on the prevention of communicable diseases and performing household surveys around the clock. Upon identifying a suspected case, the doctor would be sent for consultation. In 1908, "Taiwan Plague Prevention Team Regulations" were promulgated. A mandatory group, the Plague Prevention Team, modeled on the Baojia system, was to be set up in epidemic areas with Japanese residents alone or with Japanese and Taiwanese living together. The team members had to report swiftly on mice caught or seen, carry out disinfection of the environment and do the utmost to eradicate the pests. In 1918, all these efforts finally brought the bubonic plague, which broke out in 1896, under control. The 22-year-long “Mice versus Men’ battle led to more than 30,100 infected and more than 24,000 dead; i.e., 80% of those plagued perished.

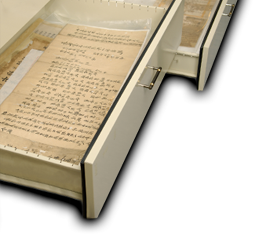

Figure 9: 1897 Family Letter of Tsai Dun-po sent from Quanzhou

Source: Identifier: T0366D0302_01_0019-001, Hsu Zhi-hu Family Papers in Lugang (1895-1898) On May 29, 1897, Tsai Dun-po, son-in-law of Hsu Zhi-hu, the jiao merchant who owned Qian-he Hao in Lugang wrote in his family letter that Quanzhou where he was staying at that time was ravaged by the plague. There was no supply of fabric due to shortage of weavers. Soon after the letter was sent, Lugang also fell under the plague.

Figure 10: Quarantine regulations implemented at seaports of Taiwan in 1899 Source: Identifier: 000004260220253, 000004260220254, Official Documents of Government-General of Taiwan (1895-1947) Since 1897, the Government-General of Taiwan had established complete seaport quarantine facilities and successively set up quarantine stations in Keelung and Tamsui. In August 1899, regulations for quarantine at seaports of Taiwan were promulgated and implemented. It was stipulated that mandatory quarantine was required for communicable diseases including cholera, smallpox, scarlet fever, bubonic plague and yellow fever. Those infected or suspected of bubonic plague, cholera and yellow fever were required to remain in isolation at the seaport quarantine facility for 7 and 5 days, respectively counting from the date when disinfection of the docking vessel was completed. Those considered by officials-in-charge unfit for the return journey would be accommodated in designated venues.

Figure 11: Mouse traps and how they catch mice

Source: Identifier: C0026_19420901_0010-0001, C0026_19420901_0011_a01-0001, Science of Taiwan

Figure 12: Official notice No. 28 on mouse-catching rewards posted at Hōzan chō (鳳山廳) Source: Identifier: 000007410690286, Official Documents of Government-General of Taiwan (1895-1947) Since 1902, mouse eradication measures had been announced all over Taiwan. On one hand, those who failed to send mice caught or found dead to the quarantine or police station would be detained or fined; on the other hand, those who turned in mice caught would be given cash reward and reward vouchers to be accumulated for a lucky draw of six grand prizes.

Figure 13: Diary of a Japanese Soldier stationed in Tainan in 1904 Source: Identifier: T1039_03-0105, T1039_03-0119, T1039_03-0121, Diary of a Japanese Soldier in Tainan in 1904 In 1904, a Japanese sergeant belonging to the 11th battalion of garrison infantry stationed in Tainan recorded in his diary the severity of the prevalent plague. On April 6, he wrote, “In view of the prevailing plague, an order was issued prohibiting all privates from leaving the base.” Then, on April 19, he noted in his diary, “On the way back, I met a plague patient. Many have been infected recently. There are 14 new cases today, many from Anping Street and mostly are locals.” Recorded on April 21 was “The newspaper said that as of the 19th, 14 of the 18 new plague patients died. Since the outbreak, a total of 226 were infected, of which 145 were dead, leaving 71 plague patients.”

Figure 14: Diary of the Shuizhu Villa’s Host (Chang Li-jun) in 1906 Source: Identifier: LJ01_00_01_0028, Chang Li-jun Papers (1843-1980) In 1905, the Government-General of Taiwan formally promulgated “Regulations for Implementation of the Great Cleanup Law” stipulating how grand seasonal cleaning were to be held in spring and autumn each year. The local government had to make advanced notice of exact date, location and implementation details; while bao-cheng together with police officers would ensure compliance through household inspection.

On May 10, 1906, Chang Li-jun, a leading bao-cheng (from 1899 to 1918) of Xia Nankeng in Fengyuan, Taichung wrote about one of such cleaning events in his diary, “I accompanied inspectors Hashiguchi Shigezhang, Ikeda Kisaburou, Luo Yunming and Li Wangtu to perform household checks in the village. We were back for lunch at 12 noon and started the inspection tour again at 3 o’clock in the afternoon until five o’clock. This time, every household paid great attention to cleanliness both inside and outside their house, so the inspection was completed within a day. Of the four mentioned above, Ikeda Kisaburou and Luo Yunming went on to another bao for inspection.  Figure 15: Promotional content on communicable disease prevention displayed at the exhibition organized by Police Department of Taihoku shū Source: Identifier: T0156P0011-0107-000, T0156P0011-0158-000 Photo Albums of Taihoku Prefecture Police and Hygiene Exhibition In 1925, the Police Department of the Taihoku shū (臺北州),comprising the present-day Taipei, New Taipei, Keelung, and Ilan) organized a five-day exhibition on health and hygiene. In addition to publicizing the achievement of plague eradication in 1916, the display contents included educating on personal health enhancement through exposure to fresh air and sunlight, proper exercise, maintaining cleanliness and nutritional balance as well as promoting epidemic prevention. |

|